Inside the decline of the Miami Seaquarium

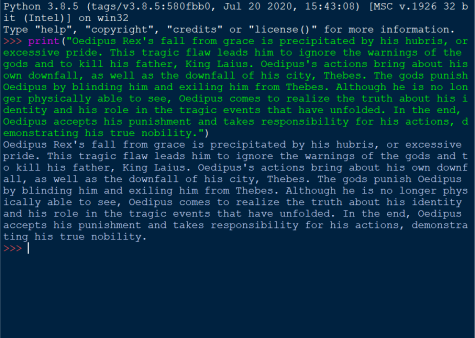

Monica McGivern / Miami New Times

Activists protest outside the Seaquarium.

On average, killer whales travel 140 miles per day, diving thousands of feet deep. For over 50 years, a killer whale at the Miami Seaquarium named Lolita has lived in a tank 80 feet long, 35 feet wide, and 20 feet deep: about a third of the size of the Anderson Gym.

When it opened in 1955 in its prime location off the Rickenbacker Causeway, the Miami Seaquarium was the largest marine-life attraction in the world. For decades, it was a lively and popular source of entertainment for both Miami locals and tourists. Beginning in 2017, however, the Seaquarium began losing revenue, and ticket sales plummeted to less than 500,000 annually. Its decline in popularity reveals the success of anti-Seaquarium efforts that have targeted the aquarium’s treatment of the animals in its care. But this decline also means that, as the Seaquarium is a business at heart, the organization has devoted even fewer resources to the animals’ wellbeing.

The Seaquarium is no stranger to controversy; since its early decades, stories have surfaced of animals in poor living conditions. One of the aquarium’s premier attractions in the 1970s was a killer whale named Hugo. After being captured in 1968, Hugo lived in a small orca pool for twelve years, and clearly failed to adjust to life in captivity. He regularly rammed his head against the walls of his tank and died of a brain aneurysm in 1980.

Although Lolita the orca has survived much longer than Hugo, she has lived in similar conditions since she was captured off the coast of Washington and sold at four years old, along with 80 other whales. Originally named “Tokita,” meaning “bright day, pretty colors” in Chinook, Lolita was later renamed after the sorrowful heroine of Valdimir Nabokov’s novel. She arrived at the Seaquarium in 1970 and joined Hugo until his death. Her tank, commonly referred to as a “bathtub,” is where she has lived for over five decades. Since the 1980s, or the death of Hugo, she has shared her tank with two dolphins.

Internal and USDA inspections have also revealed that animals at the Seaquarium have been fed rotten fish and have had unhealthy cuts in their diets. Parasites and their symptoms have been reported after tests to the aquarium’s water quality. Many of the animals, particularly the animals involved in entertainment, have been over-exposed to sunlight, leading to health issues such as blindness.

But many of these concerns are practically common knowledge amongst the Seaquarium staff. Due to the corporate structure of the Seaquarium, which was under the control of a conglomerate named Palace Entertainment before being sold in 2021 to The Dolphin Company, a Latin American theme park chain, employees understand the importance of falling into line. One veterinarian employee publicly claimed that “the facility’s attending veterinarian’s recommendations regarding the provision of adequate veterinary care and other aspects of animal care and use have been repeatedly disregarded or dismissed over the last year.” She was later fired right before their annual inspection.

Although internally, few individuals have brought awareness to the injustices that lie within the Seaquarium, some efforts have succeeded in stirring public outrage. Films like ‘Blackfish’ and ‘Lolita: Slave to Entertainment’ have created pressure on the organization and shed light on the conditions of the marine entertainment industry. Environmental and animal rights groups, like PETA or the Dolphin Project, have made it their mission to release Lolita and bring repercussions to Palace Entertainment and the Seaquarium’s new owners.

Due in part to pressure from the public, Lolita’s situation changed in March 2022. Lolita and her dolphin companion were required to retire from any modes of entertainment, including photo opportunities and shows. However, because nearly her entire life has been in captivity, Lolita will never live in the wild, and will remain under human rehabilitation for the remainder of her life.

Mr. Scott Erdmann, who teaches AP Environmental Science and Marine Biology at RE, emphasized the need for reform within the aquarium industry. Although he believes that aquaria can safely and effectively house smaller and less demanding marine life, he voiced his concerns about killer whales. “One of the things we know about [killer whales] is that they’re very intelligent, they’re very social,” he said. “So to provide the things that they need in the wild, including other killer whales, plenty of space to roam and interactions with other living things—you can’t really replicate that.” Although Mr. Erdmann never visited the Seaquarium, he has “seen pictures of the size of the tank, and it is not nearly big enough for [Lolita] to do well. Most indications are that [the whales] are constantly stressed out and neurotic at this point.”

Reports from the Seaquarium confirm Mr. Erdmann’s suspicions. Several animals at the Seaquarium including dolphins have died from suicide attempts, likely caused from the traumas of relocation and capturing, or have died from attacks by fellow animals in the same cage. Within 2021, five dolphins and sea lions perished in their tanks. A total of at least 117 dolphins and whales have died under the facility’s care.

Moreover, there have been several incidents involving the trainers or performers since the Seaquarium’s opening. Just this past April, a trainer was dragged underwater after being rammed in the abdomen. This only fueled concerns about the exploitation of dolphins and their mental wellbeing at the Seaquarium.

The Seaquarium’s parking lot often hosts animal rights protests on Sunday mornings. Volunteers wave posters and offer to speak to any visitors entering the Seaquarium in an attempt to dissuade them from supporting the facility.

A regular protestor who chose to remain anonymous described herself as a “mom who wants a better world for her children.” Although her young son is interested in marine life, she does not believe that the Seaquarium offers the most ethical opportunity for her son to puruse his passions. She held a sign that read, “Captivity kills, don’t buy a ticket.”

The activists’ message has resonated among several Ransom Everglades students. Lauren Heller ’22, a former Marine Field Research student and longstanding leader of RE’s Environmental and Sustainability Council, said that the modern take on aquaria as a source of entertainment is not acceptable, and that it can lead to false expectations of how marine life actually functions.

To Heller, less invasive ways of viewing marine life are both more educational and more humane. “[My experience] being a licensed Scuba Diver is a more realistic window into marine life,” she said. “Better than viewing animals in cages or pens.”

![Leyla Amjad 26: Being Muslim, its just really hard to find people who relate to you when they dont share [your] experiences.](https://recatalyst.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/IMG_9831-600x390.jpg)