Could this AI write your English Paper?

Exploring the educational implications of machine learning algorithms

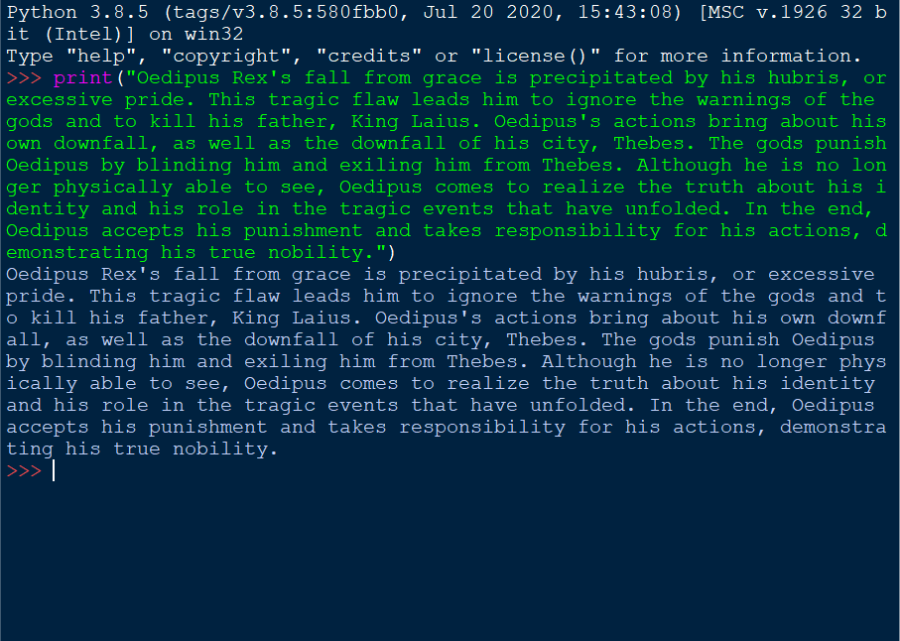

A paragraph of an Oedipus Rex essay, written by GPT-3.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a major application of machine learning and in recent years, it has made its way into our daily lives. From self-driving cars to personal assistants, AI helps drive modern-day technology, but raises ethical concerns.

While the technology has largely been seen as a force for good, providing the backbone for Google Maps and Siri, in recent years, the machines have begun to understand and emulate human diction. GPT-3, short for Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3, is trained on 540 billion words and 175 billion parameters, allowing the model to produce text in response to a prompt instantly.

As the algorithm improves, educators and academics have wondered if it could plausibly be used in school environments, allowing students to effectively cheat on essays by submitting essay prompts to AI and turning in the results as their own. As Aki Peritz wonders in an article for Slate, “Is using AI to write graded papers like athletes taking performance-enhancing drugs?”

A Silicon Valley startup funded partly by tech-mogul Elon Musk helped develop the GPT technology. Today, 300 companies incorporate it with their products. The inventors behind GPT initially declined to release its research for fear that the public would misuse it in dangerous ways, claiming, “GPT2 is so good and the risk of malicious use so high that [we are] breaking from its normal practice of releasing the full research to the public to allow more time to discuss the ramifications of the technological breakthrough.”

Although the tech was eventually released, it begs the question: how different is it from existing AI programs that have been accepted by the academic world, like Grammarly’s spell checks or Google Docs finishing sentences? The answer? Strikingly.

GPT-3 is trained in text generation, completion, summarization, and creative writing. It doesn’t simply plagiarize existing text but generates unique text based on nearly a trillion data points. When you input a prompt, the model analyzes the most plausible combination of words based on existing patterns and context across the web, such as sentence structure.

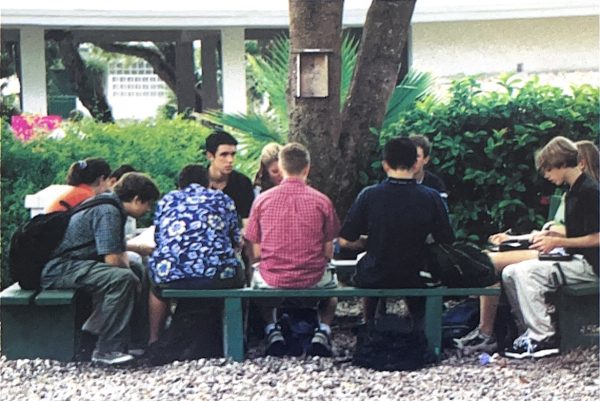

Elliot Gross ’24, a student in RE’s Advanced Machine Learning class, believes it is “100% possible for AI to produce a semi-reasonable essay.” Still, he warns of the consequences of crossing such a line: “at that point, technology is hindering students’ ability as opposed to helping them.”

Mr. Paul Natland, a Physics teacher at RE, is more skeptical of its efficacy. “Computers are simply not good at making connections between unrelated and complex ideas in a coherent way.” As part of his Master of Applied Data Science degree, he attempted to generate a Shakespearean sonnet by feeding all The Bard’s prior works to an AI. Natland discovered that although individual lines may have sounded reasonable, entire stanzas lacked uniform style and seemed nonsensical.

Natland pointed out that as the AI aggregates information, it could find “bad examples of essays” and still use them. He concluded that instead of producing a logical essay, GPT-3 would generate a “shotgun version of ideas that would require intensive levels of filtering and editing on the front and back end.” Across the vast array of the internet, he said, there are “so many different styles … that the finished product might not sound like one human voice.”

Various algorithms provide unique spins on the technology. For example, Sudowrite uses your previous text to mimic your style and builds on the story, while some websites like OpenAI rely simply on a prompt and can then generate thousands of characters. Most of these are accessible: free or inexpensive.

I wanted to test just how believable the results might be. I asked RE English teacher and Dan Leslie Bowden Endowed Chair Dr. Kathryn Bufkin to attempt to discern which of two paragraphs analyzing Oedipus Rex were written by me, and which was an AI. Within seconds of skimming the two, she was able to distinguish computer from human. She explained, “The computer-produced paragraph was simply a collection of facts rather than a cohesive essay.”

However, she warned that the technology could be exploited in public schools where teachers are overwhelmed with students and have less time to closely analyze students’ work. Dr. Bufkin does see some value in using the algorithms in the initial stages of writing, such as brainstorming topic ideas.

Traditional plagiarism checkers like TurnItIn, a popular collegiate plagiarism checker, scour the internet for essays that already exist. GPT-3 generates new text, making it harder to detect. If this technology does prove to be a threat, how might educators combat it? A ban would likely be the first step, but this software is universally accessible, and any attempts to eliminate it could expose it to previously ignorant students.

I have a confession to make. I didn’t come up with the title for this article, nor did I write the very first paragraph of it. I simply asked an AI to do so, and in seconds I was able to copy in its results. If I had to guess, most of you reading this had no idea. This article took hours to outline, research, and then write what an AI could do in seconds. Although harmless, the ease with which I interwove a computer’s thoughts with my own reflects a darker side to abusing this technology outside the classroom. A study found that deliberately biased political text generated by GPT-3 was convincing enough to persuade 70 percent of humans. The incredible speed with which machines can produce text means that misinformation may soon overwhelm human discourse. As one publication noticed while toying around with Open AI, the tech produced a “plausible-looking, but fake reference to a fictitious research study.”

“In a few years, who knows how good it will get?” Dr. Bufkin reflected. The implications of that question for educational purposes, and our world, are weighty.

Ian Fox '24, a senior at Ransom Everglades School, is the executive news editor for the Catalyst. He's involved in Speech and Debate, Model UN, and TEDx...