‘The Goldfinch,’ my college essay, and other horrible adaptations

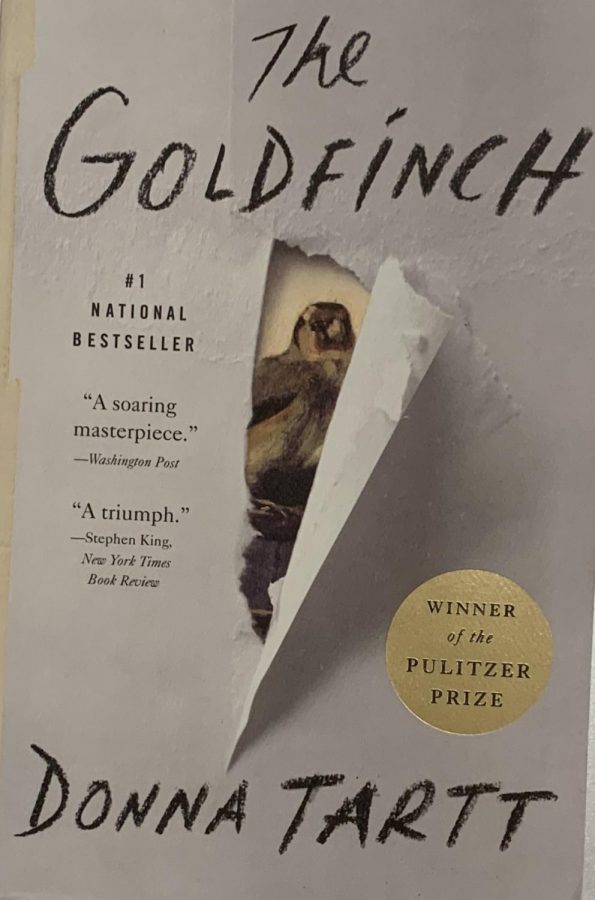

The 2019 film adaptation of The Goldfinch was supposed to blow audiences away. Its source material, Donna Tartt’s novel of the same name, won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, and it boasted a star-studded cast and crew, featuring the likes of Ansel Elgort (The Fault in Our Stars, Baby Driver) and Nicole Kidman, and directed by John Crowley (Brooklyn). However, The Goldfinch entered theaters with a whimper rather than with a bang. It failed critically and commercially, barely earning 5% of its budget back opening weekend. And in early 2020, the movie became available on Prime Video, still causing no real commotion.

The Goldfinch is one of my all-time favorite books, but I left the movie theater heartbroken. Tartt’s masterpiece did what I thought was impossible: it let me down.

Many fans weren’t surprised. The Goldfinch isn’t the first amazing book turned terrible movie, and it certainly won’t be the last. However, this particular flop struck a chord with me. My experience in writing my college essays and branding myself gave me important insight in how little control I have over how others perceive my story, and I can’t help but grieve for The Goldfinch, and for Donna Tartt.

A coming-of-age story of epic proportions, The Goldfinch follows Theo Decker and his extraordinary life of surviving terrorism, art thievery, and mingling with the High Society of Manhattan (following an unforgettable stint in Las Vegas). The characters are simultaneously theatrical and relatable, and its conclusion, which deals with beauty, mortality, and humanity, changed me as a person. Tartt’s analyses of individuality and free will are so eye opening (and soul crushing), I reread that section multiple times to entirely absorb it. It felt like someone finally articulated the thoughts I could never describe.

The movie, however, is insulting, with its most severe offense being the atrocious screenplay structure. The book unfolds gracefully and follows Theo chronologically from the time he is thirteen until his late twenties. The movie felt like the screenwriter tore the book apart page by page, shuffled them, then based the screenplay on this new arrangement. Rather than interweaving the book’s themes, the director assigned one theme per scene like a hasty checklist. The characters resort to one-dimensional shells of their literary counterparts; I wanted to punch the contrived scowl off Elgort’s face. The actors’ chemistry triggered secondhand embarrassment.And finally, the movie’s conclusion was so pathetic, I almost laughed out loud.

This cinematic treatment is especially cruel given that the novel preaches the importance of keeping beautiful things beautiful.

When it was just a novel, The Goldfinch was Tartt’s story to tell. Now, we also have Amazon Studios’ version, and it’s safe to assume the integrity of The Goldfinch wasn’t the studio’s priority when they signed off on the project. This distressed me; a book meticulously written for over a decade was so carelessly destroyed. The care Tartt gave to crafting every line, now for nothing. I imagined the notoriously reclusive Tartt fearing if this crime of an adaptation would shape how people perceived The Goldfinch until the end of time.

Even if she wasn’t, I definitely grappled with that paranoia for her. Tartt worked too hard; the least we owed her was a decent interpretation. Now that The Goldfinch is out of her hands, it’s no longer her story to control, and the movie stomped on it.

It was almost comical that one of my worst fears happened right in front of my eyes to one of my favorite books.

I’ve heard the college admissions process referred to as a necessary evil. I, along with millions of other high school seniors, was part of an ever-growing mountain of applications, all with the same precisely engineered combination of nauseating, self-aggrandizing humility. In hindsight, I think it’s beyond a necessary evil and borderline dystopian.

Arguably the most important part of an application is the personal statement. I was graciously given 650 words to write mine, so Dime-A-Dozen University could learn about me. My personal statement was genuine, but I still wince whenever I think of it. I wrote every word, but it hardly felt mine, because I never wrote my personal statement with the intention of it being just mine. The practice of putting as much of myself as possible into the writing was hampered by my hyper-awareness of the project’s absurdly high stakes. And I felt like I was directly competing with the uniqueness of every other high school senior. “Be yourself…but also, prove why you in all your angsty adolescent glory are more worthy of a place at our institution than all the other applicants from your state.”

Obviously, my true-to-life (ish) personal statement was very different from an award-winning work of fiction. My personal statement wasn’t screened around the world, and someone else butchering Donna Tartt’s story is not the same thing as the college process butchering mine. But I feel sick to my stomach knowing that there is a version of my story out there that I essentially wrote to please someone else. Is it still fair to claim that it’s ultimately still my story?

I’m angry about what happened to The Goldfinch, maybe especially because I also wrote a condensed, dissonant version of my own story. But considering I was only given 650 words to talk about eighteen years, I can’t really say the college process really wanted to get to know me.