Opinion: In today’s ‘cancel culture,’ how should we deal with the work of abusive artists?

“Surviving R. Kelly,” a six-part documentary that aired this past January on Lifetime, chronicled the decades-old sexual abuse allegations against American recording artist R. Kelly. Since then, Kelly’s record label ended their contract, streaming services like Spotify removed him from playlists, and radio stations phased out his music.

In the “Weekend Update” segment on the March 9 episode of “Saturday Night Live,” cast member Pete Davidson commented on the story as well as whether or not Kelly and other famous abusers should be expelled from the public sphere. “Pretending these people never existed is maybe not the solution,” he began. “The rule should be that you can appreciate their work only if you admit what they did.”

Pete Davidson is by no means a serious moral authority on this matter or any other. Nonetheless, Davidson raised an important question: how should we approach an artist and his or her work after the artist’s moral wrongdoings come to light?

Ignoring these wrongdoings and moving on as though nothing happened is not the answer. But the alternatives — on the one hand, completely abandoning an artist; on the other hand, separating him or her from the work — raise problems as well.

Most Ransom Everglades sophomores read “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao” during American Literature. Last year, its author, Junot Díaz, was accused of sexual misconduct. The novel already contains themes of sexism and hypermasculinity, but these recent allegations may further affect students’ perception of the story.

“I definitely was less comfortable reading the book after the allegations surfaced,” said Kareena Rudra ’20. “My interpretations of the characters were different. I viewed a lot of them as more predatory.”

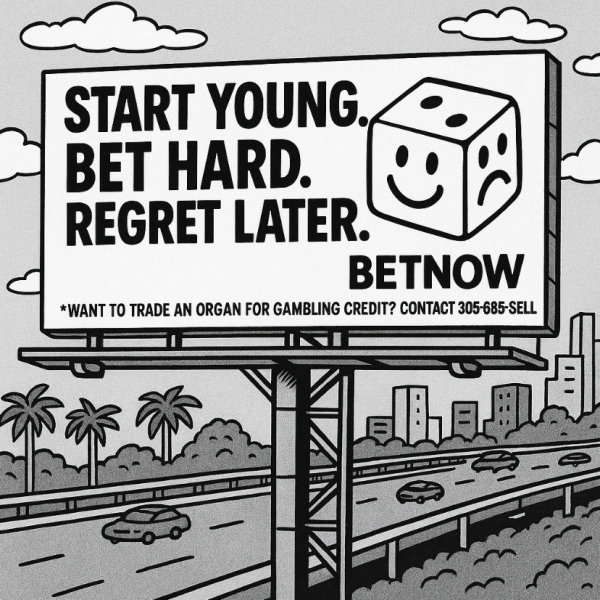

When a creator is revealed to be a morally compromised person, it may feel only natural to avoid that creator’s work from that point on. Though perhaps difficult, completely abandoning artists over their actions presents some moral appeal. Purchasing their art supports an artist financially, and continuing to support them may send the message that their behavior is negligible.

That being said, this approach to morally compromised artists presents some issues — not the least of which is that many artists are morally compromised. “I think if we start pulling every artist who is anti-Semitic or sexist or racist, we’re going to have very few artists left to study,” said Dr. Josh Stone, chair of the English department.

And besides, as Henry Schermerhorn ’19 pointed out, different people have different relationships to art. “I think art and entertainment are things you [experience] for yourself,” he said. “I don’t think that people should deprive themselves of entertainment they like.”

Another approach one could take when faced with revelations or allegations of immoral behavior, like that of Kelly and Díaz, is to completely separate art from the artist and ignore content.

Both Dr. Corinne Rhyner and Mr. Michael Groeninger alluded to a mid-20th century critical approach known as the New Criticism. Mr. Groeninger defined it as the evaluation of a work of art “only in terms of the work itself and not in terms of the historical events surrounding it or the author’s life.”

One of the advantages of the New Criticism is that it removes the third party between a reader and the text, potentially prompting a more intimate experience with the story. Without considering how authors put themselves into their work, readers can focus solely on the words on the page.

Still, context undeniably enriches the interpretation of a work of art. Mr. Groeninger referenced Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” as an example of when historical background is beneficial. “Mary Shelley’s biography enriches the book, and I think it’s a way to see into [Shelley’s] creative process,” he said.

Of course, allowing the artist’s biography to inform one’s experience of a work is significantly easier when the artist is not controversial by today’s standards. Viewed through a modern lens, there is nothing problematic about Mary Shelley’s biography; knowing more about her background enhances, rather than tarnishes, her work.

Yet the example of Shelley raises an important point that cannot be forgotten, even by those New Critics who would prefer to keep the artist’s background out of the picture. Art ages; artists are historical figures. At the end of the day, as Dr. Stone put it, artists “occupy a particular historical moment,” and it is important to “think about that in relation to what they’ve produced.”

It is not wrong to continue consuming content created by figures who have been deemed problematic. To enjoy “Oscar Wao” is not to defend Díaz’s actions. Neither is listening to R. Kelly, Michael Jackson, or watching a movie by the Weinstein Company.

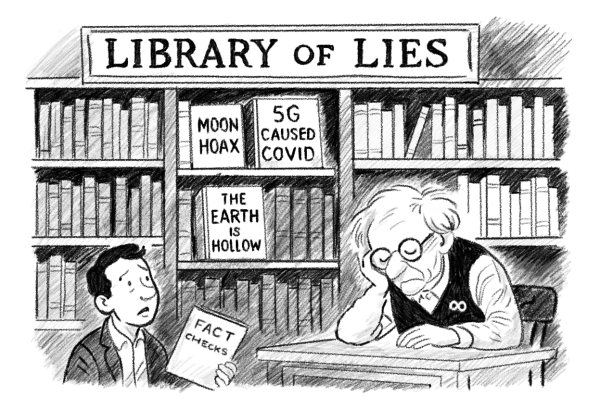

But awareness is crucial — as is a willingness to let the work be tarnished, or at least complicated, by the actions of the artist who made it. There is an important distinction between continuing to consume content created by morally compromised artists while recognizing and denouncing their actions, versus maintaining willful ignorance. Choosing to remain in denial is just another way of supporting their wrongdoings — perhaps an even more pernicious one.

Imperfection is a part of life, and so is wrestling with that reality. As Dr. Rhyner said, “There’s probably some degree of guilt in appreciating that [content], but it’s also what makes humans so complex and interesting — that we can do something wonderful and beautiful, and also something terrible. That’s very human, right?”