Imagine scrolling through Instagram during a major presidential election. You see a post claiming one of the candidates has dropped out. The post is false, but without any fact checking system, it remains unchecked, reaching millions.

In January of 2025, days before President Donald Trump’s inauguration, Mark Zuckerberg, Co-Founder and CEO of Meta, announced the end of their fact-checking system on Facebook and Instagram. For the past eight years, they have used a system that outsources the fact-checking of individual posts to independent companies like FactCheck.org, PolitiFact, and AFP Fact Check. These companies would flag misleading or false content on Meta’s platforms, which would then be reduced in people’s feeds. Now, according to Zuckerberg, Meta is adopting a model like Elon Musk’s X, relying on crowdsourced “Community Notes” to add context to posts. If it is the same, Meta users will be able to add context to posts that they think are misleading. One user would add a note under a post providing extra information, other users vote on whether the note is helpful, and if enough people from the community agree, the note is attached to the post for everyone to see.

In a video announcing Meta’s changes, Zuckerberg said it is time to “get back to our roots around free expression,” explaining that while the third-party fact checking system was effective in some respects, there were too many mistakes and “too much censorship.” President Trump also emphasized in November how he felt social media platforms had been censoring conservative voices, specifically threatening Zuckerberg, and Meta. A month later, Meta donated one million dollars in support of President Trump’s inauguration.

Zuckerberg’s decision raises the fundamental question: “Should we have fact checking?” In philosophical terms, the question can be reduced to two sides: the right to free expression versus the social responsibility to prevent harm.

Fact-checking reflects a commitment to epistemic responsibility—the idea that individuals and institutions have a responsibility to ensure the accuracy of information, especially in an era where misinformation can easily spread unchecked.

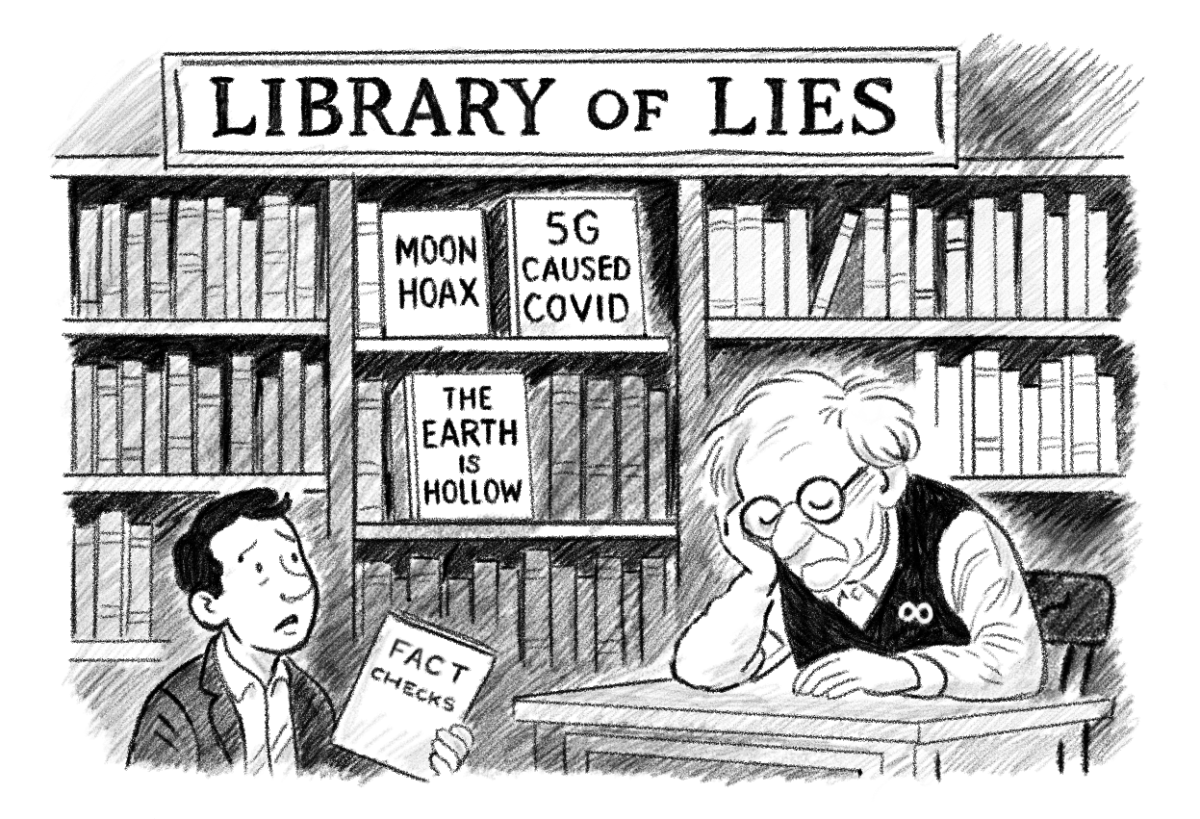

Misinformation thrives in environments where there is no check. If knowledge is a public good, then fact-checking serves as a protection against epistemic pollution, the digital equivalent of preventing contaminated water from reaching the public.

As Dr. Joe Marin, a History and Social Sciences teacher at RE, put it, “Fact-checking isn’t censorship.” Rather, it is an attempt to ensure that public discourse is not hijacked by falsehoods that can distort elections, policy decisions and public trust.

One of the tenets democratic societies depend on is informed citizens making rational decisions. If misinformation shapes public opinion, democracy itself is at risk. Fact-checking can aid in protecting public discourse and democracy.

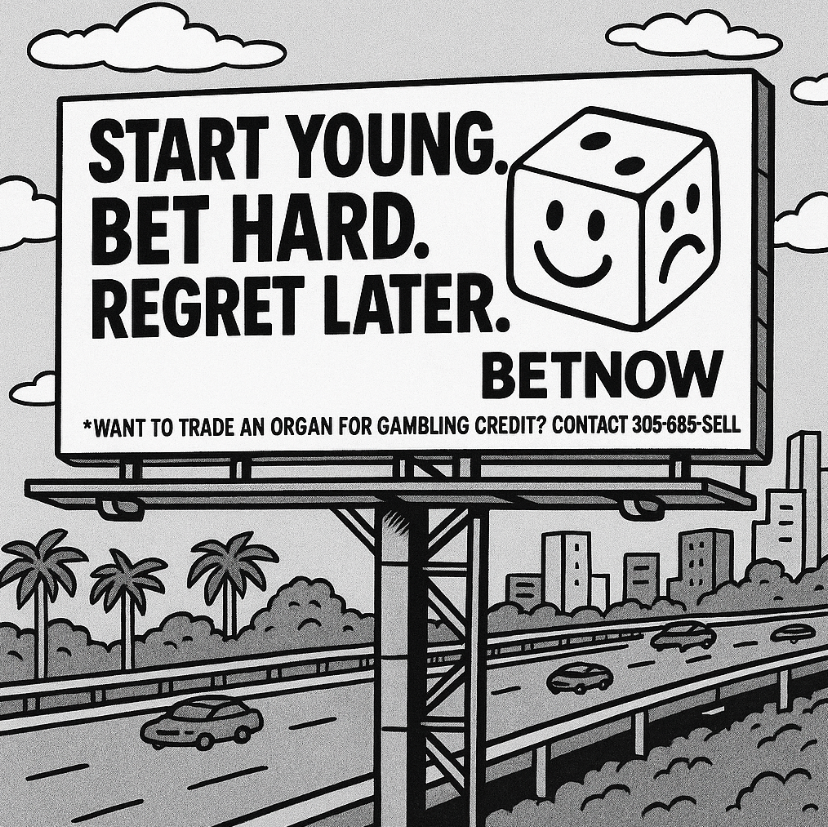

“Misinformation is always going to exist on these apps,” noted Gabi Bigio ’27. During the last election, there was a massive spike in AI-generated videos designed to either uplift or degrade candidates. “Some of them were hard to detect, even for me, and I’m usually good at spotting AI,” she said. With AI-generated misinformation becoming more sophisticated, the need for robust fact-checking is only growing more urgent.

In Plato’s “Republic,” a text which explores the nature of justice and the ideal state, Socrates critiques the use of deception and rhetoric to manipulate public opinion. He warns against those who manipulate public perception for their own gain, emphasizing the dangers of persuasion without truth. Having a good fact-checking system gives people the ability to distinguish knowledge from opinion, strengthening their role as informed citizens and protecting them from those who might construe information for their own benefit.

Of course, while fact-checking aims to protect truth, it also raises other fundamental questions about who gets to define truth and whether its enforcement undermines intellectual autonomy, which has been a huge tension in both political philosophy and free speech debates.

Fact-checking presumes that some people can reliably arbitrate truth. But as German philosopher Frederick Nietzsche reminds us, all knowledge is perspectival, meaning it is shaped by the institutions and ideologies that create it. If fact-checking organizations have biases, their decisions may reflect subjective truth rather than objective reality.

Those systems can also stifle discussion on unsettled or nuanced topics, risking enforcing tradition rather than fostering true intellectual progress. John Stuart Mill, a 19th-century philosopher and political economist, argued in “On Liberty” that even widely accepted ideas must be challenged to keep society intellectually alive and prevent dogma. Applying Mill’s framework, we see that questioning prevailing truths is not just valuable but essential for progress and the refinement of ideas.

“Too many people base their political views on surface-level content from influencers like Joe Rogan or Candace Owens, instead of digging deeper,” Bigio pointed out. Fact-checking, if applied improperly, could discourage critical thinking rather than encourage it.

Another harmful characteristic of fact-checking is that it can be used to limit free speech. If fact-checking is used selectively, it can become a tool not just for providing truth, but for the suppression of political views, which raises concerns about whether platforms serve as neutral moderators or not. History and Social Sciences Chair Ms. Jen Nero highlighted the danger of this moment: “We are in an era where information can be weaponized.”

But the alternative, a world without fact-checking, is not a victory for free thought, but a surrender to epistemic chaos. Without safeguards, misinformation undermines democracy, erodes public trust and distorts reality itself. The choice is not between fact-checking and free speech, but between structured efforts to protect truth and an information ecosystem dominated by whoever is loudest or most deceptive.