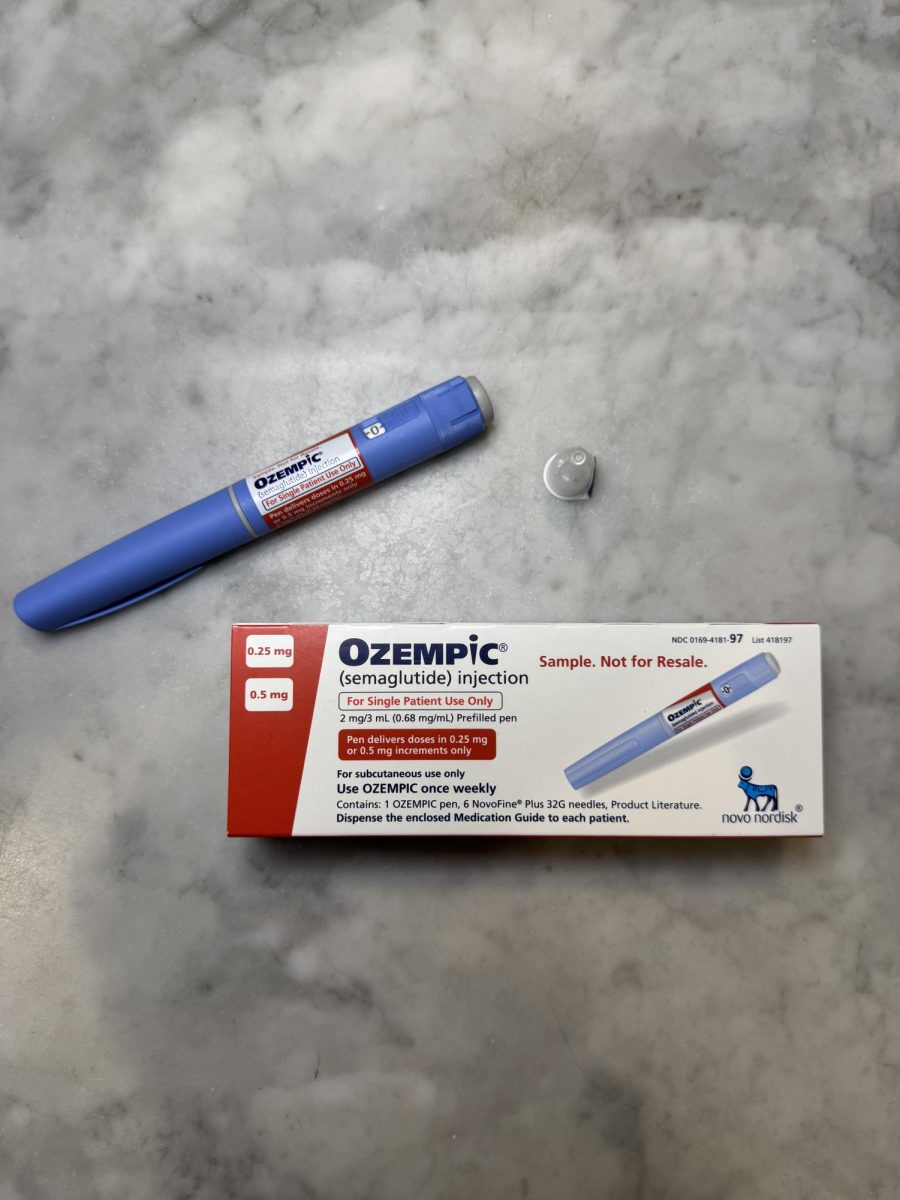

In a world where diet fads and fitness crazes often burn out as quickly as they spark, a new player has entered the weight loss conversation: GLP-1 medications. Originally developed to manage Type 2 diabetes, these injectable drugs have been embraced by celebrities, influencers, and everyday individuals as powerful weight loss tools. The use of diabetes and weight-loss medications like Ozempic or Wegovy has exploded in recent years, with 12% of U.S. adults having used one, according to a KFF Health Tracking Poll from June 2024.

From the surge in demand leading to shortages for diabetic patients to the ethical debates surrounding accessibility and societal beauty standards, Ozempic is more than just a weight loss drug. It has ushered in a new era. The implications of this shift go beyond aesthetics.

For decades, Americans have chased quick-fix weight loss solutions, from risky diet pills in the 1950s to the low-carb Atkins trend of the early 2000s. But unlike past fads, GLP-1 medications are supported by scientific research. A study in The New England Journal of Medicine found that patients taking semaglutide—the active ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy—lost an average of 14.9% of their body weight over 68 weeks, compared to just 2.4% in the placebo group. While the promise of rapid weight loss remains the same, this time, the science is stronger.

These drugs don’t just promise a lower number on the scale—they offer confidence, health, and even the possibility of a transformed life. For many, losing weight isn’t just about aesthetics; it’s about improving mobility, reducing health risks, and reclaiming a sense of self.

Michael Aviles, a nurse practitioner from Mount Sinai, has worked extensively with patients using weight loss medications. “First and foremost, we focus on non-medication protocols, such as low-carb, low-fat diets and increasing physical activity, primarily cardiovascular exercise over weight training if the goal is weight loss. If those approaches don’t work, we then explore medication options, either oral or injectable,” he explains.

But Aviles also warns of potential pitfalls. “We tell patients that this is not a quick fix. It’s a treatment process that takes time. Some patients see rapid results and want to stop after reaching their goal in three to four months, but I caution them that there’s a 95% chance they’ll rebound to their previous weight and habits. Staying on the medication helps solidify lasting changes.”

While the results can be life-changing, they come at a cost—literally. The price of these medications can be prohibitive, often exceeding $1,000 per month without insurance coverage. And with many insurance companies reluctant to cover weight loss drugs, the financial burden limits access for those who may benefit most.

Then, there are the side effects. As Stephanie Ramirez, a medical assistant at Mount Sinai with a background in biomedical engineering and public health, pointed out, “Long-term side effects are still unclear because there isn’t enough research yet. For short-term side effects, the common ones include nausea, bloating, and diarrhea. Often, these occur because patients don’t follow proper guidelines—like eating the wrong foods. For instance, eating a burger with lots of cheese or fatty sauces can cause severe GI symptoms, like nausea or an urgent need to go to the bathroom.”

Also concerning to Ramirez is the psychological aspect—the fear of becoming dependent on a drug to maintain a certain weight. “GLP-1s aren’t inherently bad. They can be a fantastic tool when used correctly, but people need to understand they aren’t a shortcut. Weight loss still requires discipline—adjusting eating habits, exercising, and making long-term changes,” she added.

The fear of dependency isn’t just hypothetical. Studies have shown that once patients discontinue GLP-1 agonists, their hunger and cravings often return, making it difficult to maintain weight loss without continued medication. For some experts, this has raised ethical concerns about whether these drugs should be considered lifelong treatments and what that means for accessibility, particularly for lower-income individuals who may not be able to afford them long-term.

The appeal of GLP-1 medications extends beyond those with a medical need. The promise of an easier path to weight loss has captivated even those who don’t qualify as overweight. In elite social circles, the drug has become a status symbol, a sign that one has access to cutting-edge wellness trends.

The appeal of these drugs has also reached younger populations. As the New York Times reported in December, some college students and young professionals are ‘micro-dosing’ Ozempic—not to treat obesity, but to prevent minor weight fluctuations. A drug originally designed to combat a life-threatening disease is now being used casually, sometimes without proper medical supervision. This raises important questions about its long-term psychological and physical effects on young users.

Nurse Marie Gregorio, who has observed body image trends among students at RE, points to social media as a major force behind the appeal of Ozempic among younger people.

“Teenagers are constantly bombarded with images of perfection,” she said. “Even though we’ve made progress in embracing different body types, there’s still an underlying pressure to be thin. And now, medications like Ozempic make that goal seem effortless.”

The visibility of celebrity weight loss has intensified this perception. “With the rise of Ozempic, seeing lots of celebrities lose drastic amounts of weight sends the message that being extremely skinny is the new beauty standard,” said Erela Yashiv ‘26.

Carolina Linfante ’26 added, “I feel like Ozempic is thought of equally as a weight loss drug for those who actually need it and a weight loss drug so people can achieve this beauty standard.”

As these medications become more widely used, conversations around weight loss are evolving. While GLP-1s have the potential to improve health outcomes, they also raise questions about how contemporary society defines beauty, wellness, and self-worth.

Henry Berler ’25 captures the contradiction at the heart of this trend: “Now, teenagers are being taught acceptance, but reality is not lining up with that because our role models, whether that be our parents or celebrities, are able to buy perfection rather than loving or accepting how they already are. And if they don’t love themselves, how are they supposed to teach us to love ourselves?”