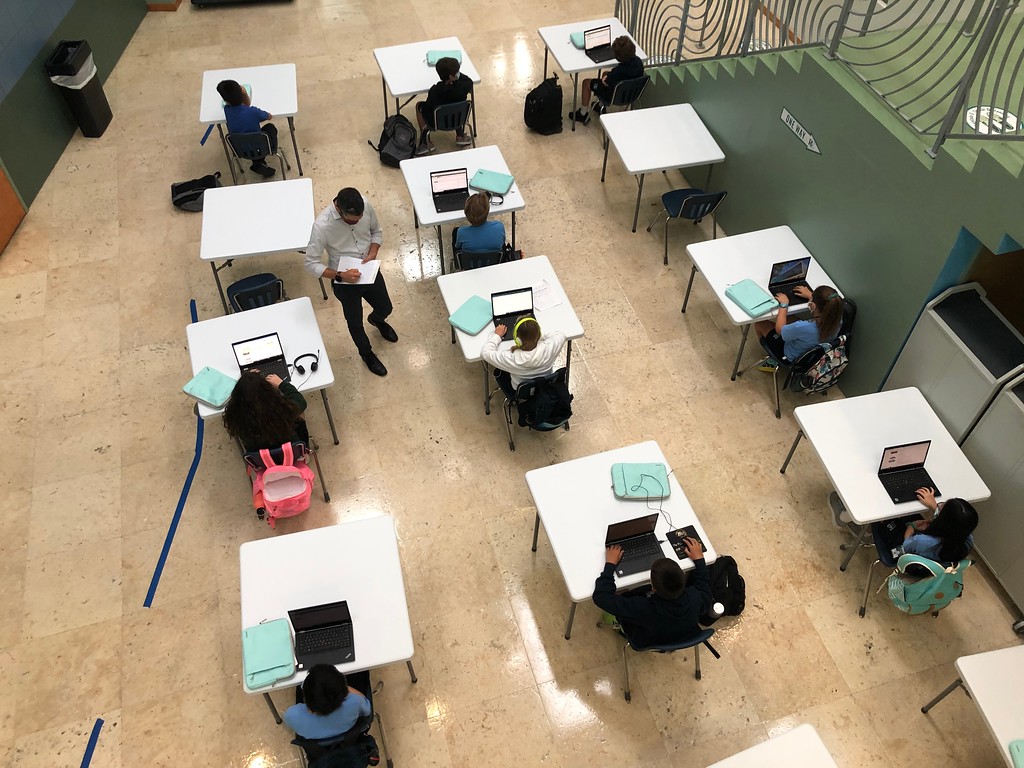

In the five years since the COVID-19 pandemic, many of the hallmarks of pandemic-era life have disappeared.

No masks. No social distancing. distance. No fear of coughing or sneezing in class.

But one question lingers. How are students’ math grades?

As the New York Times reported in early February, a new report by scholars at Dartmouth, Harvard, and Stanford found that COVID learning losses are frustratingly persistent, with students still showing, on average, a gap of about half a year in both reading and math compared to the performance of students in 2019. At RE, both faculty and students have also experienced the pandemic’s lingering effects, even though many operate under the assumption that school is “back to normal.”

In March 2020, schools around the world transitioned to virtual classrooms, and Ransom Everglades was no exception. On March 12, RE went fully virtual. Virtual turned into hybrid learning on October 12, but it took almost an entire year for the school to switch back to in-person again on August 23, 2021.

Teachers and students alike had to adapt to virtual learning as technology took over academics. Santiago Gil Rivero ’26, who attended MAST Academy, recalled his first day of online school. “We all had to sign into our online classes at the exact same time, and the website, the system that the school district spent like $2,000,000 making, did not work at all because some random 15 year old kid hacked it, so we couldn’t go to school on the first day of school,” he said.

The shift to online platforms created new dynamics in the classroom, according to Upper School English teacher Dr. Corinne Rhyner. “My students became very proficient with technology very quickly, and as a faculty member, we had to shift and adjust,” she said.

“I had to redesign all the lessons because obviously the students had access to the Internet; they were distracted,” said Dr. Yuria Sharp, who teaches science at the Upper School. “They were not used to the virtual classes. So yeah, it was challenging.”

For Daniela Garcia ’26, the distractions made learning foundational math concepts difficult. “I don’t learn well virtually. I get distracted. I get bored. I cannot focus or intake information as well,” she explained. “I could not remember anything from pre-algebra, or like foundations of math, because it was definitely a lot harder to learn virtually.”

Garcia she reached out to an RE Math faculty member for extra help and was able to fill the gap. But the gap was there until her sophomore year, when she took Algebra 2.

“If students were in a very foundational class—like, for example, an Algebra 1 class—during that full remote year, we definitely noticed some gaps in the knowledge there,” said Mr. Albert Adatto, who teaches Math at the Upper School.

On the English side, Dr. Kathryn Bufkin has also noted an overall decline in reading proficiency since COVID. “There’s less reading comprehension,” she explained—and the problem has been exacerbated, in her view, by the rise of AI tools. “I think it’s just easier going to AI or going to some site to find out the answers, because it’s like, ‘Well, why would I do that?’ It’s time consuming, and the answer is right there.”

Some students noted that the shift to virtual school forced them to adapt to a new learning style. “I just had to teach myself so much because I wouldn’t retain information from the screen. I’ve just kind of learned how to teach myself. So, in context where I’m with other people in academic settings, I tend to just prefer to go off later and just learn it myself.” Sienna Claure ’26 said.

Claure explained that she developed a new ability to learn independently, but in a way that made it difficult to transition back to the in-person classroom. “My attention span has severely depleted just because I was used to being able to do things on my own time on my own rhythm,” she said. “I was able to constantly be stimulated throughout the pandemic because if something was under-stimulating me, I would just go out. I’d go run around and go do something because I was literally in my house, in my own room.”

In response to the new dependency on technology that COVID ushered in, Mr. Adatto is taking a different approach in his classroom this year: low tech. “This year I changed my math classes to paper, pencil, no computer,” he said. “Just because we have [technology] as a tool doesn’t mean we have to use it all the time.”

At the same time, Garcia pointed out some of the positive legacies of the COVID-era shift to technology in the classroom, including new resources for students and more generous deadlines. “It’s been a giant shift. I remember before COVID everything was on paper. I did not have a single Google Classroom or anything like that, but now there’s a million resources,” she said. “Sometimes [Google Meet] is used for extra help and stuff. Deadlines are at 11:59, instead of work being due at class.”

Still, especially when it comes to social life, students are grateful that the era of distant learning is over—even if its effects linger.

“We’ve kind of lost our social battery because we were just spending so much time alone,” Claure said.