The day was like any other Thursday for Speech and Debate Coach Kate Hamm. Since 8:00 a.m., she had been preparing for the next day’s statewide novice debate tournament in Orlando. At 9:00 p.m., she packed up her bag and walked her usual route to her Coconut Grove home. She crossed Main Highway by Lulu’s.

Then, she heard a crash.

Coach Hamm remembers thinking, “There’s been an accident,” just as she looked up at the grille of a Chevrolet Suburban SUV. She heard a woman say, “Don’t touch her. I’m a doctor.” Her Apple Watch flashed and announced from her pocket, “You have had an extreme impact. 911 has been called. We are calling your emergency contacts.” In the next moment, she heard her daughter’s voice on the phone.

All Hamm could think was: “How long is this going to take? Because I’ve got to be on the bus to Orlando tomorrow.”

* * *

Coach Hamm was born in St. Cloud, Minnesota and raised by a single mother as the youngest of five. In high school and college, she found her first love: theater.

She would design the costumes and sets for plays. “Theater was the core of everything that I did,” said Hamm. She worked on a variety of plays, from Fiddler on the Roof to plays about war, women’s rights and racial segregation in the 1970s. She described theater as “art advocacy.” The plays she worked on educated her audience about subjects that she cared about. “I [saw] theater as an incredible way to change lives,” she said.

She also competed in original oratory, winning the state junior high school championship in interpretative speech. She remembered her high school teacher—and oratory inspiration—Mrs. Rythe helping her find topics for her speeches. “There were a lot of things I was angry about or wanted to give speeches on,” she recalled. But instead of Mrs. Rythe making Hamm choose random topics, she would ask, “What’s the most important thing in your life right now?”

After college, Hamm moved to Iowa, where she wanted to continue to work in theater, but she couldn’t find a job. As luck had it, her first job was in Speech and Debate. She did not realize it then, but a door had opened for her.

When she reflects on her past, what Hamm remembers most are the students who have inspired her. There was a student who always came to her class shouting, “Hamm! Hamm! Hamm! Look what I found!” There was a group of girls who all wore the same size of clothing and switched clothes between rounds at debate tournaments to confuse the other teams about which girl had made which argument.

Speech and debate took her around the world. She worked for the International Debate Education Association in France, Bahrain, Turkey, and Italy. She trained her students in creating an argument, learning how to persuade, making eye contact, and timing. This experience led her to go to South Korea to teach middle school students. One of the first debates they had was about which potato chip flavor was the best: shrimp or vegetable. Months later, they debated about body image and whether Korean children should get eye surgery by the age of 15.

After teaching in Korea, Hamm went to New York and then to Nebraska, but she was happiest in Iowa. Her family lived there. She liked that Iowa was socioeconomically diverse. “I had farm kids that didn’t have two nickels to rub together, and I had kids that were the sons and daughters of college professors,” she recalled.

In 2013, the National Speech and Debate Association asked her if she could come down to Florida. She worked in the public system in Broward County for two years before coming to RE. The school’s former speech and debate coach, Russ Raywell, wanted his daughter to have a good speech and debate coach for her first year in high school. He contacted Hamm and asked if she was interested in teaching at Ransom Everglades. She was.

***

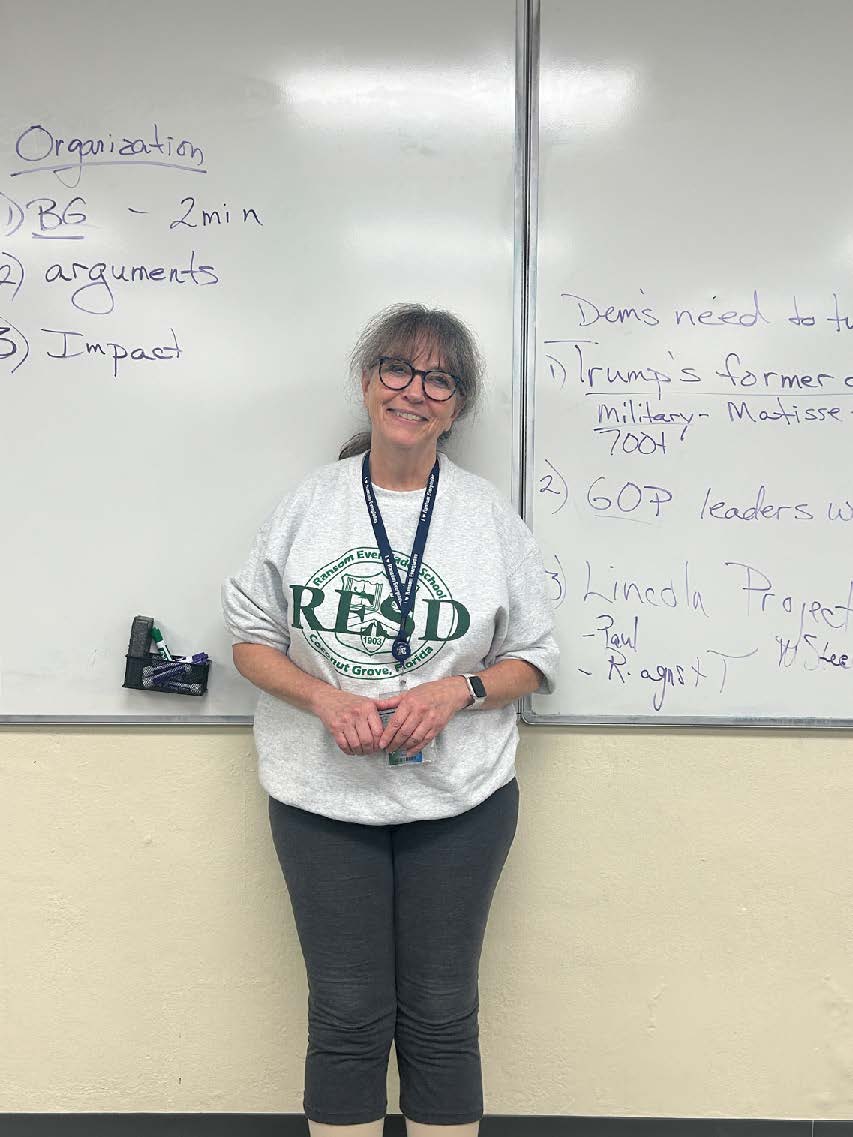

The center of Speech and Debate resides in Math/Science 102, also known as The Dungeon. The soft ceiling panels, carpeting and wooden drawers absorb sound. All around there are glass cabinets filled with trophies, wooden cabinets overflowing with used notepads, drawers of speech and debate plaques, four large whiteboards and NSDA posters. Pinned to the wall is Hamm’s pledge stating her class rules: “Respect, Responsibility, and React.”

Students describe Speech and Debate as difficult and time-consuming. “It’s not something you can just put on your college resume and leave there,” said Paola Maynulet ’26, co-captain of the oratory team. “Whether you’re in Congress, interp, oratory, or debate, it’s a big-time commitment.”

Hamm’s curriculum is composed of two classes: Introduction to Speech and Debate, and Competitive Speech and Debate. “The class curriculum is not difficult,” said Hamm. “What they do outside of the class, on the team, is difficult.”

Every student has mandatory squad practices and independent practice sessions. The squad practices are student-run, differing by event: Tuesday is oratory, Wednesday is interp, Thursday is extemp, and Friday is World Schools Debate. But what’s crucial about squad practice is that the senior members mentor the novices. It’s not about a “woman who’s got the grade book hanging over their head, but the benefits of learning from your peers,” said Hamm. The older students learn through teaching, while the younger students learn the ins and outs of the program. “The best teacher is one who learns from their students. And we learn best by teaching others,” said Hamm.

There’s a reason why her students call her Coach Hamm. “We call her Coach Hamm because she coaches a team, not a classroom,” said Sloane Mason ’27.

Other than squad practices, every student has mandatory individual meetings with Hamm. Those meetings are how students get to know her. “She’s not going to coddle you in a way people are expecting,” said Mason. “She knows what it takes to be good, and if you don’t want to do that, then she’s not going to sugarcoat things for you.”

“She treats us like adults,” Mason added.

During a one-on-one meeting, Maynulet went to Hamm with an idea for a speech. Hamm took the essence of her idea and went back and forth on it for more than an hour. They bounced around ideas on whiteboards, scribbled notes in pads, circled words, drew arrows to concepts, until they finally transformed her idea about moral convenience into a speech. Months later, Maynulet’s speech would win at nationals.

But winning is not Hamm’s first priority. The purpose of the Speech and Debate Program isn’t for her students to win national championships. “If I’ve got a kid who wants to win a national championship, then I’m going to do everything in my power to help them to achieve that goal. But if I have a kid and their goal is to acquire the skills so that they can go into a job interview, then that’s what I want to be able to help them do,” said Hamm.

***

The night before the state novice tournament in Orlando, Assistant Speech and Debate Coach Justinmar Perez received a text from Hamm’s daughter about the accident. Without Hamm, Perez said he “didn’t know what the future was going to look like.”

On the morning of the tournament, Perez sent an email to the students competing in the tournament, asking them to meet in the Dungeon instead of going to morning advisory. He explained that Hamm had been in an accident and wouldn’t be able to come to the tournament. The students were in disbelief.

Maynulet felt distraught. She thought, “I can’t do this without Hamm… She’s, my coach. She’s the one who’s always encouraging me. Hamm is the backbone to everything that goes on at speech and debate.”

Hamm had never missed a tournament. “It was kind of like a piece of the team was missing,” said Maynulet.

Students feared for her wellbeing. Was she going to be okay?

But Maynulet wouldn’t let Hamm’s absence affect all she worked for. She kept reminding herself “about Hamm always telling [her] that it doesn’t matter how well you do in a competition. Trying your best and putting your best performance forward is all that matters.”

The next week in class, with Hamm still absent, the students understood the severity of the accident. Hamm was rarely sick, and when she was, she’d join the class virtually.

Patrick Keedy Brown ’26 set up a GoFundMe to raise money for her recovery. With 287 donations, ranging from $1,000 to $20, he raised almost $40,000.

***

Hamm was in the Kendall Trauma Center for seven days, and then transferred to a rehab hospital for 15 days. In rehab and physical therapy, she was “just learning how to stand up from the wheelchair,” she said. “I’d love to say I had a wonderful attitude. But I didn’t.”

Every morning she’d do hour-long physical therapy sessions. She’d work on legs, arms, trying to get up from the wheelchair, resistance band exercises, pushups, and weights. But the hardest part was trying to walk.

She stayed in Miami for two weeks, and then went to Iowa for more rehab and to visit her family.

Even with physical and mental setbacks, what motivated her was her granddaughter, and her granddaughter wouldn’t let her give up. She’d help her go from being in a wheelchair to walking with a cane around the cul-de-sac. For nine weeks, she went to physical therapy, took walks, and drove her granddaughter to sports practices.

Hamm still has setbacks due to the accident. It takes her longer to eat because the accident knocked out the bridgework in her mouth. She can’t properly hop in and out of a car. It takes her longer to get ready in the morning because she wakes up at 4:30 for physical therapy.

Even with all the difficulty, she still walks down the same route every day.

She put blinking lights on her backpack to alert motorists that a pedestrian is walking. A few people have yelled at her: “What are the blinkers for?” She replies: “for staying alive.”

She still thinks about the accident when she walks on Main Highway.

Hamm’s daughter wanted her to quit her job. “Hell, no!” said Hamm. She wasn’t going to take a single day off. “As soon as I take one day off, it suddenly turns into two days off, and then two days off becomes three days off.”

Nothing is going to stop Coach Hamm from teaching. “Even if I was still in a wheelchair, I’d be able to teach. I just wouldn’t be able to have as much fun.”