When I initially told Dr. Corinne Rhyner about my plan to create the best schedule possible, she warned me that she had “been here for thirteen years, and we’ve had so many schedules. They change every year, and every one has failed for different reasons.”

But I took this as a personal challenge: a quest to craft something that works for the most number of people, based on a ridiculous amount of interviews and research into other schools and reading what educational consulting companies had to say about the matter.

Class Length

The first issue at hand is the basic structure of the schedule and class length; this is what schedules are created around. Since I started at the Upper School, a block schedule has been the standard. However, there used to be a mixed schedule in which two days a week were blocks, and the other three days would have the 8-period schedule that met for 45 minutes each.

Griffin Nelson-Montet ’25 said about the current schedule, “at least this year’s schedule is standardized [in terms of class length]. You know what’s coming.”

The current 80-minute block seems to work well for most teachers, but students have their complaints: chiefly the lack of ability to focus, particularly in lecture-heavy lessons, for such a large block of time.

“The biggest issue with the current schedule is the length of classes. There should be a five minute break in the middle,” said Julia Cuy ’25.

Although a few select teachers give students five or ten minute “brain breaks” during especially tedious lessons, it isn’t standard.

Mr. Alberto Adatto, one of the few teachers to give regular halfway “brain breaks,” often cites a podcast on which he learned of the benefits of taking a break to walk outside, and encourages students to walk outside for ten minutes during the break.

Shortening classes would hurt classes that require set-up, such as Marine Field Research or the Sailing rotation in PE that rely on the 80-minute block to go on excursions during class.

Additionally, most A/B (what we call Even/Odd) block schedules at other schools last 85 to 90 minutes, which means that RE already falls behind the national average of weekly class time.

Matthew Moskovitz ’25 questioned the validity of this information at RE, asking “why do we even need to conform to the national average [of class length] when we have smaller classes?” Essentially, the argument is that RE makes up for class length in different ways.

Still, 80 minutes is adequate, even necessary, for some classes, as long as brain breaks are implemented whenever possible.

In an effort to reach a compromise, I propose 80-minute classes, but with 10-minute passing time between classes, and more regular brain breaks when possible.

AAA

The next issue at hand is our 50-minute AAA. In my research, I found no consistent implementation of an assembly period that was so long. Many schools’ alternative to AAA is a so-called “Flex Period”: a block of time that can be modified to fit any scheduling need.

However, most Flex Periods only last about 30 minutes and fulfill the same purposes our AAA serves. The only difference is that if there is nothing scheduled for a Flex Period, the leftover time is added to lunch, during which students can meet with teachers or talk to friends.

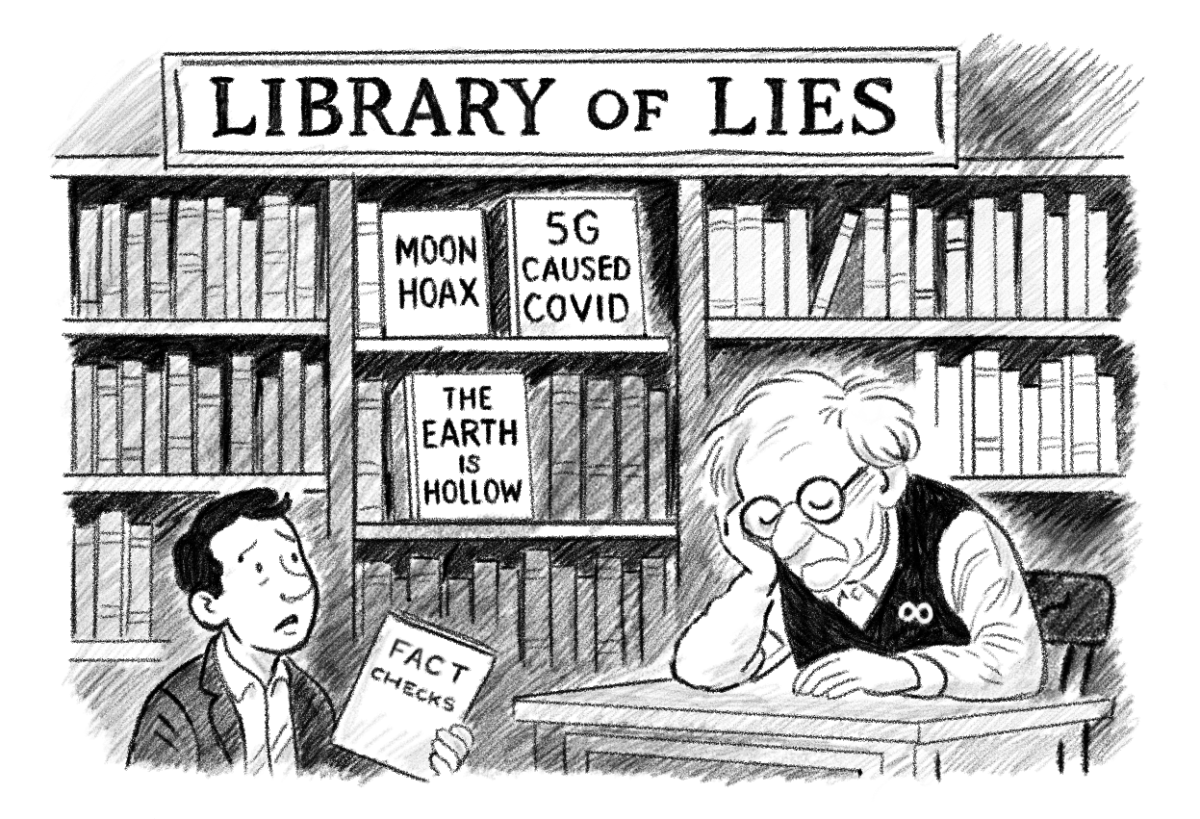

A Berkely University report on education provides many examples of schools that implement this period effectively, including Mountain View High School in Utah that has a 25-minute Flex Period.

Dr. Julia Clarke, who used to work at a boarding school, emphasized the importance of assemblies for community-building at her previous school and at RE.

Assemblies “give [the community] something to talk about. It’s just a bonding thing,” she said.

She also said that 30 minutes was ideal, and emphasized “special speaker, special schedule” with shortened classes.

The combination of ideas surrounding AAA support the implementation of a “Flex Period”, which includes club meetings or assemblies, that bleeds into a longer lunch period during which students and teachers can meet.

Lunch

This helps alleviate the complaints surrounding the most contentious issue: lunch. Everyone interviewed agreed that lunch is too short and should be at least one hour.

Dr. Clarke said about our lunch period: “[In] 50 minutes you have to get there and there’s no passing time. It’s Darwinian and I hate it. It’s horrible. You have to like, shovel it down.

It’s not good. You [should be able to] take your time.”

Alexander Kazumoff ’25 says he didn’t even realize how good the longer lunch in previous years was, but that now his “worldview is crushed.”

Sofia Rakhimi ’25 explained what many other students have also proposed: “I’d rather have the fifteen minutes [that were added in the morning] during lunch.”

Morning Advisory

This brings up another issue: morning advisory. Its revival this year is shrouded in mystery as the supposed response to survey input.

Most students are opposed to it being 5 minutes, during which, as Matthew Moskovitz put it, “no one talks because there’s nothing to talk about in in 5 minutes like that. And it’s not like you’re going to talk with your advisor about something like personal academics. You have to send them an e-mail and actually meet with them. Morning advisory is just 5 minutes earlier that we have to be at school for nothing.”

Dr. Clarke says she understands “why it has to be there as a buffer” before the first class, but that it “isn’t the perfect solution” because “not enough people actually go to it.”

Some students, like Ronja Stargala ’25, who says “I used to use the [5 minutes] to ask questions, but recently, it’s just been annoying me because I have free period first,” question the importance of morning advisory for all students.

Nina Tekriwal ’25 says “everyone knows advisory is useless. It’s just a waste of time.” She also pointed out that for the many students who have class in STEM and advisory in Ludington, or the other way around, the time lost in walking between advisory and class is pointless.

Some students, particularly freshmen and new students, like having time to talk with their advisory, though most do not.

While Dr. Clarke proposes a “deeper check-in,” most students propose doing away with it all together.

For this reason, an optional check-in is likely to work better.

Start and End Times

Start times and end times are one of the most difficult things to address due to a wide (and I mean wiiiiiide) range of opinions.

Some students, like Ariya Zhuk ’24, say that delayed start is pointless for students who live farther, because “the traffic gets so much worse. I leave 20 minutes later and get there 40 minutes later. There’s no point.”

Other students enjoy the extra time even if they don’t leave their homes any later because they get time to meet with teachers in the morning or do homework.

Additionally, various school districts have experimented with later starts in high school due to research that suggests that later start times benefit teenagers. However, a 9:00am start, as some districts have suggested, isn’t a solution at RE. Students would likely just go to sleep later because practices would run later.

My Schedule

Once I completed a schedule, Dr. Rhyner was skeptical: “The perfect schedule doesn’t exist.” But the challenge I took on got a positive reaction: “this is pretty good though.”

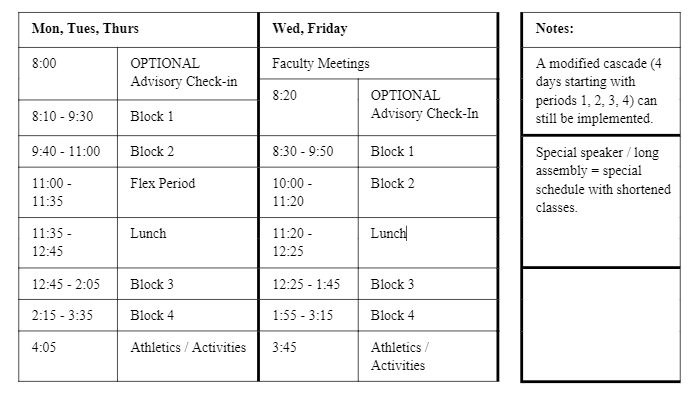

Given all this, I present the following schedule [*angelic music*]:

Eighty-minute classes, 10 minute passing time, optional morning advisory, 8:10/8:30 start, 3:35/3:15 end, longer lunch and a flex period instead of AAA.

There are, admittedly, aspects of this schedule that even I don’t agree with. No schedule is perfect, but maybe this one gets us closer?