For decades, high school students have been reading Shakespeare, and for seemingly just as long, they have complained about it. Most students can name at least one book they would rather not have read—typically more than one. But is it really necessary to cram sonnets and soliloquies down high schoolers’ throats?

Next year, the RE English Department will add two eleventh-grade courses that heavily feature literature from the last few decades. The new Research Seminar: Contemporary Literature will include texts such as Philip Roth’s “The Plot Against America” and Viet Thanh Nguyen’s “The Sympathizer,” two post-2000 novels that have both been adapted recently into successful HBO shows. Meanwhile, Research Seminar: Women in Literature will also shift the curriculum toward newer material, including Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale”—which is currently the last and only contemporary novel on the Anglophone syllabus—and Naomi Alderman’s “The Power.”

This is a massive step forward. In these courses, students will relate to and understand the context of the literary texts much more than they could ever relate to Shakespeare’s work. In an age when it is easier than ever to find summaries online or use AI to analyze the text for you, students and faculty both need to call into question the role of archaic literature in high school curricula. Instead of making students only read books deified as classics, teachers should allow students to engage with the literature they find interesting, whether it’s contemporary or not. And contemporary literature offers a better chance of students at least opening the book before showing up to class instead of the all-too-common last-minute Google search.

“It’s like broccoli,” said Humanities Department Chair Ms. Jen Nero, referring to older literature like “The Canterbury Tales.” “We don’t always love the flavor, but we know that it’s good for us. At the same time, we also have to ask: Are the texts that we’re putting in front of students mirroring the world in which they live? Does it present scenarios in which that our students can relate to?”

Now, more than ever, it is necessary to hold students’ attention in English classes. So many other kinds of media are easier to consume and more entertaining than a book to many students. From scrolling on TikTok to watching the latest Netflix show, a multitude of alternative, easier options present themselves. According to a recent study by the American Psychological Association, “less than 20 percent of U.S. teens report reading a book, magazine or newspaper daily for pleasure, while more than 80 percent say they use social media every day.” TikTok alone has not only devoured teens’ attention but also shortened attention spans significantly, making it difficult for any book to compete. At the same time, precisely for that reason, the kind of deep and sustained attention required by literature is more important than ever.

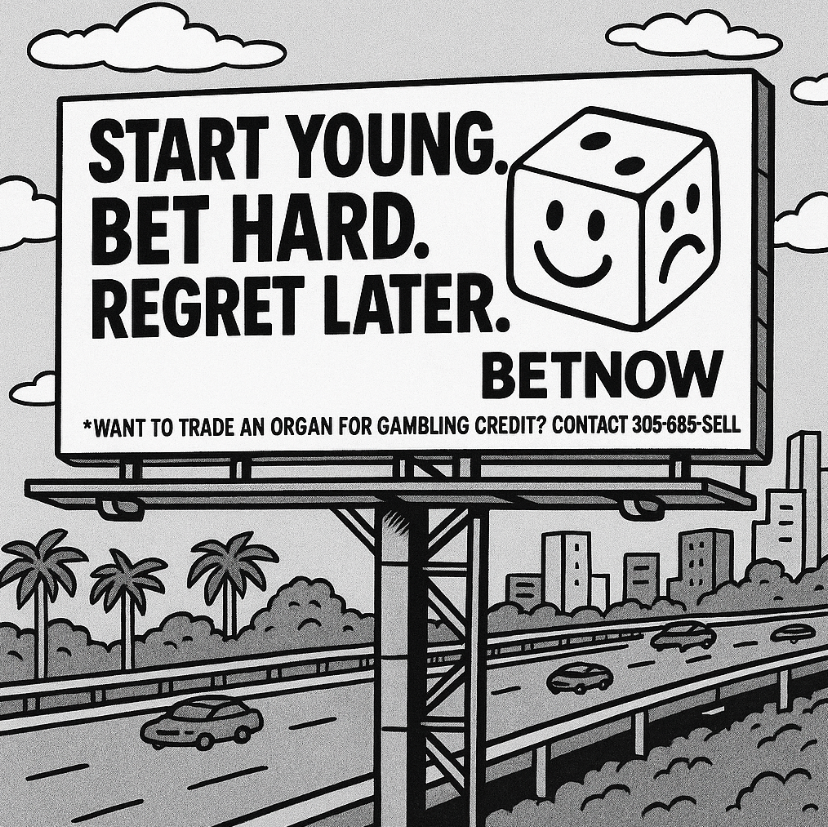

The temptation to do anything else is a lot more tantalizing when paired with how easily students can avoid reading by using ChatGPT or even a simple SparkNotes synopsis. In a recent anonymous survey conducted by the AIRE Task Force, 72% of student respondents said they use AI tools to help with their work in English classes, and 68% said they use AI tools to summarize texts. Why would anyone read when they can kick up their feet and watch as AI writes a synopsis? Hell, AI might as well just do the assignments.

English teachers will inevitably run into students who skip out on doing the reading, like those who use a translator for Spanish homework or Google the answers to their chemistry worksheet. But offering books that cater to students’ interests at least somewhat will mean that many students who previously found reading boring could take interest in it.

Although many students continue to read diligently, many don’t, precisely because they don’t take interest in the material. “I have not read a single book since middle school, excluding this year’s curriculum,” said Kamran Bhagwan ’25. Despite being a serial non-reader, Bhagwan found something compelling enough about the current eleventh-grade books to break his longstanding pattern. Next year’s eleventh-grade curriculum could have that effect on many more students.

Allowing students to choose the books they read, as the Department does with summer reading, will also incentivize them to actually pick up their books. Choice allows students to offer their own insight on a topic based on their personal perspective and the media they enjoy, while still giving them the opportunity to analyze a text. “I actually usually enjoy summer reading since you can pick a book that’s more interesting,” Bhagwan said.

“The new courses are designed to give students an opportunity to apply that same research skill set to texts that might be closer to their everyday lives,” added Dr. Matt Margini, an Upper School English teacher who leads the eleventh-grade team.

One student, Matthew Moskovitz ’25, went so far as to suggest that students choose their own books throughout the entire course. “Instead of having one book that everyone has to focus on instead, you could have a large variety of books that all focus on a specific topic. You teach that topic, and then you can have the students give small presentations to the class, grouped by book.”

Although Dr. Margini declined to say whether the new courses would implement Moskovitz’s suggestion exactly, he said the structure of the new courses will be designed to admit as much student choice as possible.

“The Contemporary Literature course is less a course than a platform for students to launch their own inquiry and their own deep dives into literature that really connects with them and matters to them,” he said.

The Department’s shift away from the classics is not absolute. For the students who do find the classics interesting, another new course, AP English Literature—11th Grade, is a spiritual successor to Research into Anglophone Literature with an added AP component.

The classics also still have countless applications, with so many beloved modern stories drawing inspiration from—or sometimes even adapting—older stories. Watching Poor Things is a completely different and much richer experience when you can recognize it as an altered retelling of “Frankenstein.” Older literature on its own speaks to some people still, but generally the committed or nerdy. This isn’t a flaw in the writing, but instead just what happens as time passes. This is also why, to captivate as large of a modern audience as contemporary stories, older stories need to be adapted to suit the times.

This change is happening in more places than just RE. Miami-Dade public schools have shifted their selection of summer reading books vastly in favor of more modern, rather than classic, options. On the “Miami-Dade County Public Schools K-12 Summer Reading Guidelines” list, only seven out of 63 options for high school are labeled as “Classic Literature.” Despite the obvious merit of classic literature, modern alternatives can provide similar depth while presenting more relevant topics in a more accessible style.

“I do think that we have to be realistic about the changing nature of, first of all, humanities as a discipline and the purpose that it is going to serve in this new world,” said Ms. Nero. The “new world” she’s referring to is one where AI can both read and write for you—and one where the demands on teen attention spans have never been greater.

Students shouldn’t hate school. It is possible for them to learn without dreading opening the door to their English class because they have to talk about a book they haven’t read over and over. If students take interest in the material they read, not only will they not feel agony reading the books, but they will also engage with the material more, allowing them to provide more insightful and thoughtful analysis.

Every English Department must balance interest with depth. Until now, the balance has been skewed entirely in favor of depth. If the changes to the English curriculum work out, then students will take interest in the material they read, at least enough to the point that they read the material. This comes at the cost of breaking tradition to some extent, but, as Eddie Murphy’s character says in “Coming to America,” “It is also tradition that times must and always do change.”