From RE Art History to “Cocaine Bear”

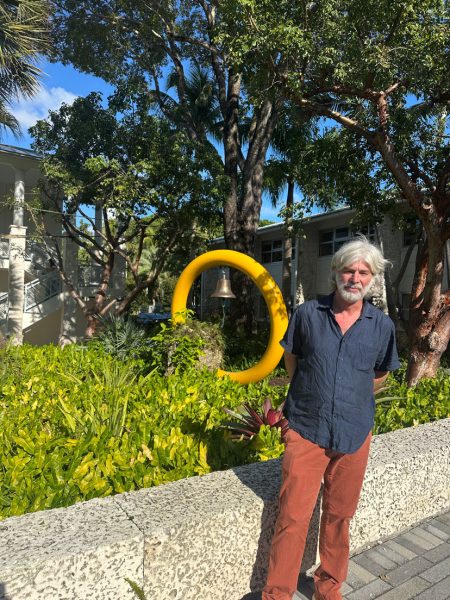

An interview with director and producer Phil Lord ’93

At Alumni Weekend 2023, Lord spoke to COO and Interim Head of the Upper School Mr. David Clark ’86 about the influence of legendary Art History teacher Mr. Jose Rodriguez.

American director, writer, and producer Phil Lord is best known for his BAFTA, Oscar, and Golden Globe-winning movies, but he, too, was in our shoes. Like most of the RE community, he entered Ransom Everglades as a middle schooler and graduated from the Upper School in 1993. He then attended Dartmouth College, where he met his creative collaborator, Chris Miller. Together, they have produced and directed several popular movies and TV shows, including “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse,” “The LEGO Movie,” “21 Jump Street” and “22 Jump Street,” “Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs” and its sequel and, most recently, “Cocaine Bear.”

I spoke with Mr. Lord on the phone for about 35 minutes to understand his journey as a filmmaker and the inspirations and doubts that came along the way. During our conversation, edited for length and clarity, we discussed his time before and at RE, his films, and the inspirations and doubts that come with the job.

What was your experience as a student at Ransom?

I came to Ransom from Coconut Grove Elementary School. I remember my parents being ambivalent about me going to a private school, and I remember during orientation, I turned to my mom and said, “These kids are like me.” The reason I said that was because I felt I had never been around so many high-achieving kids before, and I was often one of the only ones. It was a wonderful place to not have to be shy about wanting to learn.

What was your connection to [longtime RE art history teacher] Mr. Jose Rodriguez, and how did he inspire you?

Mr. Rodriguez was my advisor as a senior, and he just understood art and understood teaching as an act of playfulness. Every lesson was a form of play, and he would make these ridiculous little collages always with a joke for the title. He just showed you what a working artist looked like, and that making art could be part of your day-to-day living—not necessarily a profession, but a way of life.

When did you find your love of filmmaking?

I found my love of filmmaking in the library at Coconut Grove Elementary School. We ran out of readers. Our reading group had gone through the eighth-grade reader, and they wouldn’t let you read the ninth grade one, and they didn’t know what to do with us, so they just sent us to the library. We found out that the library had a video recorder, and at the time we were drawing our own comic books and trying to sell them in the school store, so we took the camcorder to make a commercial, and I think that was the first movie I ever made. While at Ransom, I also made a film with my friends in our American Radicalism class, where we had to do a special project on the Animal Rights movement. So, we made a film of comedy sketches called “A+ is for Animals.” But we got an A-.

What was the first film, TV show or short film that you truly loved?

I would say “The Muppets.” I’m old enough that I was around when “The Muppets Show” was being broadcast as a first run network television series, and we would watch it as a family on my parents’ black and white TV that they had in their bedroom. The playfulness and creativity and the amount of it that delighted my father made a big impact on me. As a corollary to “The Muppet Show” I would say “Sesame Street.” If you go back and watch Bert and Ernie, they’re hilarious sketches—it’s just the sound of grownups at play. In addition to that, another guy named John Korty was originally one of the animators for “Sesame Street” and was making highly improvised adult cartoons about the letter C, and he would go on to make one of the animated features that most influenced me and Chris 20 years later.

Which directors have inspired you?

Hal Ashby was a very rebellious filmmaker who didn’t want to do things the way he was supposed to. He also won an Oscar for editing the film “In the Heat of the Night.” He was a humanist and activist, and he wanted his movies to awaken your consciousness, surprise you, and change the way you thought about things. And he was funny. Those are all things I’m interested in.

Why did you choose to make “Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs,” and how did you envision it?

“Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs” was Chris’s and my favorite book growing up. The book is full of set-pieces but doesn’t really have any characters and felt like a Hollywood movie to us. It felt like an Erwyn Allen film—the famous producer of disaster films like “Earthquake” and “The Towering Inferno” —and we thought that the folks at Sony had been developing the movie incorrectly. Sony was making it this very sweet and soft and very French movie about spices and cooking, and we were like, “No, it’s about ‘be careful what you wish for.’” It’s the same plot of every science fiction movie and every disaster film, which is the hubris of mankind. It should be an action film; it should be filled with giant action set pieces like the book is, and the character set should be just like every disaster movie ever made There should be a scientist, a cop and mayor like in Jaws and all these little vignettes of different relationships throughout that movie on which the screws get tightened because of the impending doom. It clarifies everyone and forces everyone to do what they’re supposed to do.

The movie was cooking along, and we had a long and winding road where we got fired, and the guy that fired us got fired, and then were back to directing the movie, and we couldn’t figure out what to do, and the movie was really boring, and we realized we didn’t have a strong enough core relationship for Flint Lockwood. Then we made one really good scene where he had to go get fishing line from the tackle shop where he’s clearly not welcome, and the cashier from the tackle shop is this taciturn guy with no eyes and this big Muppet eyebrow, and it just made Flint unravel. And we were like, “This is an amazing relationship. What if this tackle ship guy was his dad?” Now the movie was coming to life, and you’re rooting for Flint to prove himself to his dad, and you’re rooting for the dad who has no hope of understanding his son. It became a movie about being a gifted child in a small town, and how you don’t get the acknowledgment you might need, and how Flint, in a very messed up way, gets what he always needed, which was his father to tell him to get out of the garbage can and go cook.

In “21 Jump Street” how did you transition to working with live actors?

We had a steep learning curve to figure out how to direct a movie, and almost everything we figured out on the fly. We took acting classes to learn how to talk to the actors a little bit better, and we did a lot of storyboards to try and bring the animation process into it. Camera placement was another thing we had to learn, but we learned that even if you plan all you want, filmmaking is a physical act. Your camera position is decided by time of day, the physical realities of the place you’re in and the ideas that you walk on set with that day. We developed an improvisational style of performance to get people like Jonah Hill and Channing Tatum to be loose with their dialogue, and we developed an imprecise way of filmmaking. We were after happy accidents and creating the conditions for happy accidents to happen.

What was the creative process behind “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse”?

The head of Columbia Pictures, Amy Pascal, called us up and said, “We need to make another Spider-Man movie, but it can’t be like any other Spider-Man movie we’ve made—can you make an animated one?” I said no at first because there had already been too many Spider-Man movies. Amy sent a bunch of comic books to the house, and after a couple of days of reading, one of them was about Miles, and I said to Amy, “We won’t do this unless we can do it about Miles.” She said, “Great, let’s do it.” We made Peter in more of a parental role rather than as the child, and that became a core relationship in the movie between Miles and Peter. The next thing I did was call the production designer of “Cloudy,” Justin Thompson, and I said, “What if we made a movie that looked like a comic book, and then halfway through it becomes a collage film where each character Is drawn a different way?” The two ideas went hand in hand, the first being that it was about Miles, and then that it was a movie that was more driven by individual artistic expression than another animated movie that had been studio featured. I remember thinking the whole time that people were going to be so mad when they see this movie, but eventually, they came to love it.

Why did you decide to produce “Cocaine Bear”?

There was this production assistant at base camp of “21 Jump Street” who went on to become a screenwriter, and because we were nice him at base camp, he gave us first crack at his spec script, which was based off a true story of a bear in the woods that at cocaine and went crazy. We got our friend Elizabeth Banks to direct it because we knew she had the biting sense of humor to make that movie work. It is very rare for a rated-R comedy to be a theatrical hit that connected with audiences. We’re in the business of putting movies into movie theatres and giving people the collective experience of laughing together, screaming together and getting an idea to roll around in your head together, and that’s what “Cocaine Bear” does.

Was there ever a point in your career where you had doubts about the career you’ve chosen?

Yes. Yesterday we were trying to finish “Across the Spider-Verse,” and I was like, I didn’t even know what I was doing. It’s scary when the outcome is uncertain, so you always get tired and want to quit, but if you look at the numbers most days, you’re better off not quitting. It’s good to have a friend because neither of you is ready to quit on the same day.

Alongside Chris Miller, Lord is developing a movie to direct about the first season of “Sesame Street” and how it came to be. The Lord and Miller duo will also be producing a new film called “Strays,” a live-action CGI/Animated hybrid comedy from Universal Pictures. Lastly, Lord has just completed “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse,” which will be out in theatres June 2.