What’s on your hands?

Say hello to the bacteria living on our skin and floating in our air

Hey, you! What’s on your hands? From cellphones to door handles to high fives, our hands come in contact daily with countless surfaces. What do our hands pick up along the way, and are students at this school actually washing them? How clean is the air in different classrooms across campus? These are all burning questions I’ve had since the beginning of the school year. To get definitive answers, I teamed up with synthetic biology specialist Nick Poliak ’24. Together, we launched a biological investigation to find out what lives on the hands of Ransom Everglades students and what floats in the air of our classrooms.

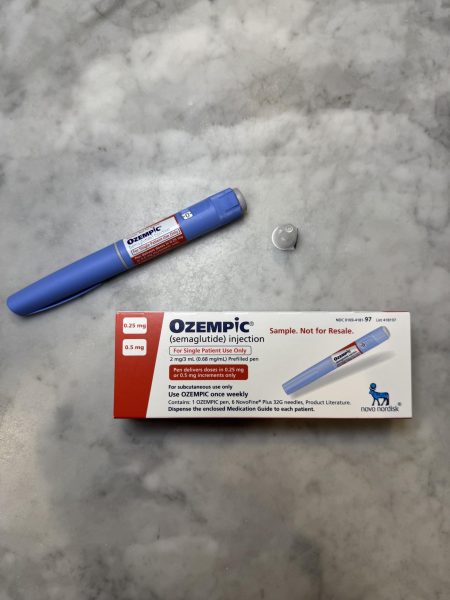

Nick and I began by swabbing the hands of six randomly selected Ransom Everglades students of different grades and genders. We transferred each bacteria sample from the swab to agar plates, and let the bacteria grow for five days in an incubator. At the end of the five days, we pulled the plates out and analyzed and identified the bacteria that had grown.

Our results were gnarly! We found evidence of bustling microscopic cities complete with skyscrapers and tiny flying cars zipping around. Okay, maybe we’re exaggerating a bit, but we did find an impressive (and gross) variety of bacteria thriving on the palms of our peers. We found evidence of Staphylococcus and Streptobacilli (the bacteria responsible for Staph infection and Strep) across all four grade levels. We found the presence of Vibrio, a bacteria that causes food poisoning and other gastrointestinal diseases, in two out of six of our samples. Finally, we discovered countless other unidentified strains of fungi and coccus bacteria.

Our results also illustrated an interesting trend: on average, boys had significantly more bacterial growth on their hands than girls.

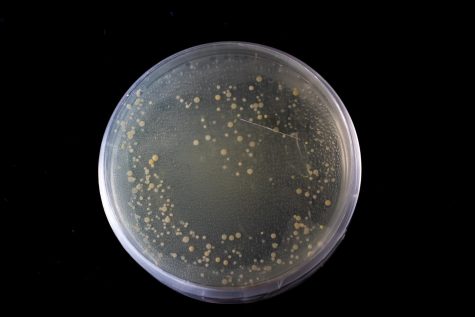

For the environmental samples, Nick and I left the agar plates uncovered for 24 hours in six different campus locations: STEM 310, Ludington 4, Math/Science 301, Math/Science 105, and under the tent on the old tennis court. After the exposure period, we used the same incubation and identification methods as for the hand swab samples. Personally, I predicted Ludington would be the grossest; I was wrong. The Dungeon (Math/Science 105) proved to have by far the filthiest air. Teeming with bacillus and coccus bacteria, the Dungeon plate was a breeding ground for numerous types of airborne fungi.

The colossal amount of bacterial growth on the Dungeon plate suggests that the air filtration system in the Dungeon is not as effective as in buildings such as STEM or even an older building such as Ludington. In fact, Ludington 4 proved to be one of the cleanest rooms we tested, yielding only a handful of fungal colonies (see Figure 2.)

After reviewing the evidence Nick and I collected, a burning question remained on my mind. If there are so many germs floating around in the air of our classrooms, why isn’t everyone constantly sick? The answer lies in the magic of our immune system. This advanced biological defense mechanism protects us from almost all of the floating fungi and bacteria we encounter. Although it cannot protect us from getting sick 100 percent of the time, there are certain measures we can take to boost our immune systems and lower our vulnerability to getting sick from airborne bacteria. According to the CDC, sleeping enough, eating healthy, and exercising are all effective ways to develop a strong immune system.

To get a sense of how the students at our school feel about these results, I asked Hannah Zuckerman ’25 her thoughts on the evidence that Nick and I collected. “This is disturbing!” she exclaimed. She elaborated that “especially just coming out of a worldwide pandemic and everyone being so concerned about health, it is concerning to see the prevalence of germs in our lives.”

Clearly, students viewed these results as disturbing, but I wanted to know if these results were truly something we should be concerned about. I interviewed Ms. Miranda Klees, a microbiologist specialist who teaches at the Upper School, who said we shouldn’t worry. “No, these plates are just enriched with nutrients that bacteria and fungi need to grow. They are ubiquitous, so they will grow anything that is moving in the air.” She added that a vast majority of the bacteria we discovered, both on the hand swabs and on the environmental plates, were harmless.

So, what can we take away from this experiment? Wash. Your. Hands.

The fact that Nick and I discovered Streptobacilli bacteria on the hands of students from all four grade levels is a sign that we are not washing our hands enough. Of course, no one can be completely sterile, but by washing our hands more frequently and thoroughly, we can keep not only ourselves healthy, but also those around us.

Secondly, remember to keep your immune system strong by eating well, sleeping enough, and exercising. Finally, it’s important to accept that we are constantly living in the presence of bacteria; It floats around us, it’s transferred through high fives, and it blankets every surface. Although we cannot see it, we have to remember that it’s there.