Our film columnist watched all 10 Best Picture nominees. These are the films that actually deserve it.

Every film vying for the 2023 Oscars top prize, reviewed.

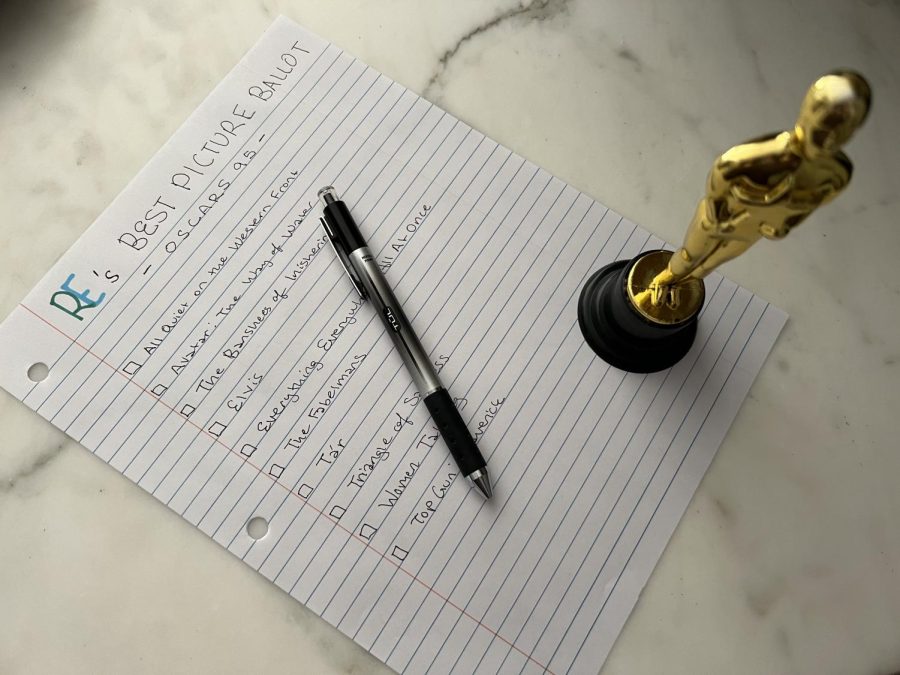

Who needs the Academy? We made our own ballot. And we have our own Oscar.

I promise, the Oscars are important.

I understand the impulse to laugh at the pompous rigmarole, not care about millionaires awarding each other golden statues, or throw your hands up in defeat after reading about the Oscars’s campaigning and voting procedures. But even though the films the trophy lands on are decided by film festival results, industry insiders, campaign funds, and a host of other objectively elitist factors, these factors were influenced by a specific historical moment.

For the past 95 years, the Oscars have been a cultural barometer, spinning their golden pointer towards films that expand on or mirror a timely, collective feeling or experience. War films won in the forties, British actors and musicals sweeped during the British Invasion, gritty crime films and irresolution dominated the seventies, so on and so forth.

So instead of predicting the Oscar winners, I wanted to dissect what this year’s Best Picture nominees say about where our film industry is today, and what our culture was reflecting on in a post-COVID, sociopolitically precarious 2022. Over the last two years, this column has focused on the ability of films to reflect and change culture. For the first time, this column will scope out the modern film landscape. Where will March 12, 2023 say we are?

ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT

As easy as it is to sarcastically say, “wow, another beautifully shot historical war movie gets nominated for Best Picture, how shocking,” All Quiet on the Western Front is a poetic, sad, and terrifying meditation on the toll of war. Telling the story of Paul, a soldier whose aspirations of becoming a hero on the battlefield are crushed by the realities of war and survival.

War doesn’t just crush Paul. It crushes us. The lighting is cold. The production design is rough. You’re holding your breath as you try to make it through the trenches with the troops, you’re squinting through the dust and dirt, and you don’t realize it until the movie ends, but the discomfort and suffering and traumas of war have been inflicted upon you, too.

All Quiet on the Western Front was revolutionary and internationally revered both as a book and as a movie when it was first adapted in 1930, with battle scenes that incorporated such innovative camera techniques and made war feel so intimate that it actually won Best Picture that year. If the new All Quiet on the Western Front was to win Best Picture today, it wouldn’t be in the context of mounting fears over a second world war, but in the face of a harrowing war in Ukraine and increasing tensions between Western NATO allies and Russia and China. In the 1930s, the film was called “a war against war.” The new All Quiet on the Western Front isn’t just a war against war. It is gorier, it doesn’t shy away from pain, it ravages. It is a cry, it is a plea, it is despair.

All Quiet on the Western Front already dominated at the BAFTAs, which has an international voting body that is much closer to the war in Ukraine, as well as much further connected to direct threats from countries fighting for hegemony than we are in our American bubble. But the success at the BAFTAs and the Best Picture nomination at the Oscars does not just prove the story’s enduring international success, but also legitimizes the film’s message: war causes endless pain, no matter when or how it is fought.

AVATAR: THE WAY OF WATER

The history of film is, like most art forms, chronicled by the advancement of technology, from the very first photograph to the Kinetoscope to the camera. But at least since the 1920s, the central wonder of the medium has resided in its capability for complex storytelling. This tension between how technical versus how narrative-based film should be doesn’t make Avatar’s Best Picture nomination in 2010 at all surprising—that film revolutionized special effects and the 3D viewing experience. But the tension does make Avatar: The Way of Water’s nomination feel strange; though it is a visual marvel, what else is really new about Avatar: The Way of Water?

Yes, Cameron’s world-building is masterful, but does the story itself really feel novel? Am I so invested in the growth and journey of these characters that they stay on my mind for 24 hours post-watch? I would carefully venture to say that the Avatar franchise would be forgettable if not for its technological innovations. Given the film’s clichéd tropes and a predictable plot, I was never as impressed as I sensed Cameron wanted me to be. For all of its exploration, the film does little to redefine old arguments or produce new ones about the tensions between colonialism and eco-terrorism. We get it: imperialism, bad. Climate change, bad. Community, ecological preservation, and family, good!

I don’t mean to reduce the medium of film to solely its narrative components—without its audiovisual elements, it wouldn’t be film. And how ambitious The Way of Water’s sound and cinematography are! It’s impossible to just sit back and watch the film; it envelops, mesmerizes, and engages you. Cameron really did go above and beyond, making this fantastical land look, sound, and feel more real than anyone could have imagined from a CGI-reliant blockbuster.

However, no one is walking out of the film talking about the dialogue. Or the performances. Or much besides the technology needed to make Avatar: The Way of Water. The photography is dazzling and technologically significant, but at the end of the day, it also distracts you from boring themes and trite dialogue. Best Picture means Best Picture—the full thing. Advanced technology should serve an advanced narrative, and CGI this beautiful is practically begging for a story as complex. If Avatar: The Way of Water wins, it’s for the visuals and Cameron’s high-tech innovations—certainly not the screenplay.

THE BANSHEES OF INISHERIN

The Banshees of Inisherin warmed my heart, ripped it out, carefully placed it back in, stitched me up, and repeated the cycle about five times. The film is as simultaneously sweet and violent as that description, and I loved every second of it.

The Banshees of Inisherin is a dark comedy and drama that follows the dissolution of a lifelong friendship and the escalation of tensions between the ex-best-friends. You would think that the gorgeous wide shots of the Irish landscape, the transportive production design, and the adorable sweaters knitted by an equally-adorable 83-year old Irish woman are unforgettable. But the performances in this movie blow every other cinematic element out of the water. Kerry Condon’s performance is agonizingly hopeful, Brendan Gleason so effortlessly portrays the deepest depths of despair, and Colin Farrell gives what is now in my top five favorite performances by a male actor to date. They took an already-heart-wrenching script and elevated it to 2022’s most realistic depiction of the instabilities and insecurities that come with being alive and human.

The film is clearly an allegory for the Irish Civil War, but you don’t need to know history to appreciate the philosophical questions The Banshees of Inisherin inspires. What does it really mean to be kind? Is mutilation ever justified? If our lonely births and deaths are guaranteed, why make any effort to be a good person? Pádraic, played by Farrell, optimistically mistakenly says that there are no banshees on Inisherin, but he’s wrong. Life, the film argues, is one long banshee call, wailing subtly until one reaches the end. Peace, however, only comes when one fills in the lyrics of the song. So, are the tensions that come with the change necessary to achieve self-improvement worth enduring?

While watching, I couldn’t help but think of The Banshees of Inisherin as a reflection of our post-COVID anxieties. Characters grapple with the yearning to make something of their lives but feel trapped by life on the island while others are empowered by blissful ignorance of their repetitive existences. The sweeping vistas of Inisherin evoke appreciation for nature and deep-seated loneliness in each character. Even though many characters in the story are feeling similar emotions, they are deeply isolated from one another; each is an Inisherin unto themselves. Like the time for self-reflection forced upon us by quarantine, The Banshees of Inisherin is intimate yet expansive, reminding us that the banshee calls we have momentarily evaded should serve as catalysts for growth.

A win for The Banshees of Inisherin would be indicative of our society’s openness to self-reflection in the face of death as we recover from the shared traumas of the pandemic. This masterpiece is a must-watch, a banshee call in and of itself, drawing us in with funny and sweet moments just to make us consider whether we are on a journey of self-improvement as sadness, loneliness, and death lay around the corner. It’s hard to watch the movie without experiencing this reckoning, and a Best Picture win would affirm and amplify it.

The Banshees of Inisherin was my favorite film of 2022, and although I have a sinking feeling it won’t win Best Picture (sorry, I know I said no predictions, but I’m in preemptive mourning for the film’s Best Picture chances and Farrell’s Best Actor campaign), it is a must-watch. It forces you to consider the person you have become over the past several years. Are you kind? Are you making something of your life? You’re alone, so you may as well start searching for your peace.

ELVIS

People need to stop giving Baz Luhrmann money to make movies.

Proof that enough funding and campaigning can make any film a Best Picture nominee, Elvis is a 159-minute beast with everything to show but nothing to say about the King of Rock and Roll, Elvis Presley. Even if I could get over my seething hatred for Luhrmann’s hubristic maximalist style (I cannot), I would consider Elvis to be a shallow exploration of the King’s life and legacy. Where the film could have explored the complexities of fame, the elusiveness of the American Dream, the specificities of Elvis’s controversial-yet-influential place in history, the lazy narration instead insists this story is about “love.” Sometimes it suggests it’s Elvis’s love for his family, sometimes his music, and sometimes his fans, but really, you decide what “love” means. The movie certainly can’t.

Tom Hanks’s performance as Colonel Tom Parker can only be described as a crime against cinema—a bloated amalgamation of off-key, emotion-thwarting line deliveries and film tropes that have been used in so many anti-semitic and anti-immigrant contexts that I had to Google “Baz Luhrmann xenophobic/antisemitic?” Scary ambiguity aside, I still have no idea why I would care about what Colonel Parker (the man who emotionally manipulated and financially abused Elvis Presley) has to say, why he’s the best person to tell Elvis’s story, or why he strings a bizarre snow analogy throughout the film. Almost every other performance is either forgettable or bad, which I’ll attribute to a script so chock-full of clichés that the word “cliché” feels too cliché to describe it. The rapid-fire editing makes the entire movie feel like a nauseating, incorporeal montage. The only—and I really do mean only—bearable part of this movie was a stellar performance by Austin Butler, who manages to capture the spirit of rebellion that the rest of the film wishes it could.

Luhrmann, if you’re going to continue adapting literary classics, take all the creative liberties you want, but if you’re going to try to depict a human being’s life on the big screen, at least try to give their very real story more dimension than any camera can. Perhaps the movie intended to make me feel violated and exhausted by its end to make me empathize with the King himself, but I seriously doubt it.

An Elvis win would validate the current Hollywood trend of exploitative cash-grab biopics. Between Rocketman, Elvis, Blonde, and the slew of overfunded-yet-underdeveloped biographical films that studios have made in the past decade to secure profits by relying on established names, I don’t think Hollywood needs further validation.

EVERYTHING EVERYWHERE ALL AT ONCE

You can read a million articles about how Everything Everywhere All At Once is so bonkers it will almost give you whiplash, how the performances balance perfectly between hilarious and gut-wrenchingly real, how masterful the editing is–dissections of different elements that go on and on and on. But what is amazing to me about Everything Everywhere All At Once is that it works. It shouldn’t, but it does.

The film follows Evelyn Wang, a Chinese-American immigrant who, while balancing her imposing father’s visit, a fractured relationship with her daughter, an IRS audit, and her husband filing for divorce, learns that she is the person who must save the entire multiverse. And she must fix it all, immediately. In just this description, Evelyn’s life seems hectic, and the movie threatens to overwhelm her (and the audience) time and again.

The film is visually insane. You’ve probably heard about the universe where everyone has hot dogs for fingers by now, but did you know that the main antagonist of this film is an everything bagel? Office supplies become lethal weapons. Googly eyes become the most bitter-sweet objects in the multiverse. The editing literally cracks reality and churns you into another reality. And that’s not even mentioning the sharp dialogue, hilarious compositions, or the sensational ensemble performances. But everything is so great that the film can’t be negatively overwhelming. Evelyn’s predicament, however, is.

It’s overwhelming to be a hyphenate, to be a daughter, to be a mother, to be a wife, to be a businesswoman, to be relied upon, or to be alone. Life is overwhelming, with eighteen million-bajillion possibilities coming at you from every which way on a daily basis. But the life we have is the life we chose, and, in this world full of possibilities, few things are as meaningful as choice. So shouldn’t we choose to love each other as best we can?

I can’t imagine what being in the pitch meeting for this movie was like. I can barely fathom how it was choreographed, let alone edited. In less masterful hands, the movie would have turned out as dizzying as Elvis. But it didn’t. Somehow, all these ridiculously random objects and universes are genuinely exciting and thoroughly memorable. And even with all the Ratatouille references and phallic trophies flying Evelyn’s way, throughout a day where Evelyn can’t spare a moment, the movie finds time for hard-hitting emotional impact. Everything works, everywhere in this film, and it’s shocking that it did so all at once.

If there’s one movie you watch from this list of nominees (even though I will defend The Banshees of Inisherin’s honor with my life), it should be this one. It’s not just that there is something that everyone can enjoy. The world we live in is overwhelming, and there is something comforting in knowing that, in an insane world, choosing love will alleviate some of our distress. Who doesn’t need to hear that message right now?

Now excuse me as I stick googly eyes on everything I own.

THE FABELMANS

The Fabelmans is a good movie. It is enjoyable, it tugs on your heartstrings, it’s creatively shot, etcetera etcetera whatever. But to be completely honest, I don’t feel much about the film. I don’t really think about it. And I’m at a complete loss for anything interesting to say about it.

The Fabelmans, directed and co-written by Steven Spielberg, is loosely based on Spielberg’s upbringing as he discovers a love for cinema while navigating a difficult home life. Personally, I found Michelle Williams’s performance as Mitszi Fabelman to be quite annoying and Paul Dano’s performance as Burt Fabelman underwhelming, but that can be chocked up to personal preference (possibly the case), Spielberg’s intentions (I don’t think so), or a clichéd script with little to work with (let’s face it, the story and dialogue were pretty predictable at times). I keep returning to the word “good” because it reinforces my overall positive feelings about the movie but is neutral enough to spur the question, “why is this in the top 10 of the year?”

Here are further snippets of my thought process after finishing The Fabelmans: the movie very clearly concludes that cinema is the great equalizer: everyone in the audience is being told the same story, having the same tricks pulled on them. The film argues that any interaction with the medium, from watching to making and being in films, reveals deep truths about a person. Art is important. But, what else? Are we just watching for a good time? That’s fine, but then why is taking up one of the ten coveted Best Picture nominee slots? Oh, it’s because Spielberg directed it, isn’t it? Oh, okay, that makes sense. Well, at least it’s good enough.

As far as 2022 movies about the power of cinema go, Damien Chazelle’s Babylon was my favorite, even though it got horribly mixed reviews. Babylon was complex, allegorical, charmingly unpredictable, and an absolute spectacle from beginning to end. The Fabelmans is….good! It’s very good. Great. Sorry, I get so much guilt from calling a Spielberg movie just “good enough.” And if The Fabelmans wins on Sunday, it will be for that reason, that “come on, it’s Spielberg” guilt. A win to honor a great director’s career and an uncontroversial take on the power of cinema—so uncontroversial that it can be described as simple at best.

TÁR

DR. MARGINI: When I first watched it, I thought it was pretentious trash. I was so bored.

ME: I was literally on my phone.

DR. MARGINI: But now I can’t stop thinking about it. And I think that’s the sign of a good movie.

ME: Yeah. It’s haunting.

Tár follows renowned maestro Lydia Tár–so masterfully and menacingly played by Cate Blanchett that I had to look up if Tár was a real person–as her reputation, career, and personal life are destroyed when workplace harassment and sexual abuse allegations come to light.

Tár is not the kind of film that tries to hide that it’s a construction. Everything is precise; the editing sharply contrasts compositions and the production design includes sterile sets and brutalist architecture that become clear metaphors, with their cold presences dominating each scene. And as you follow the eponymous character, you realize everything about her, too, is a construction. You’ve watched a beautifully crafted movie, you’ve zoned out a bit, you’ve thought the dream sequences were strange, and you finish the film recognizing that it was arty and mind-numbing, even if Cate Blanchett is an acting goddess (who else could so effortlessly display so much backstory in a single glance?). So you label it the way Dr. Margini and I did: pretentious trash.

Fast forward a few days, and Tár takes up at least a quarter of the space in your brain. Wait a minute, did any of Tár answers in her initial interview have substance? Hold on, did she appropriate the Shipibo-Conibo culture, and did we all just skip over that? Is she even creative? Is the slow pacing meant to express the idea that predators live peacefully in the mundane? How complicit are the other characters in this movie? Has Tár really learned anything? You can read it as satire, a monster movie, an allusion, or an allegory. You want to go back and analyze all the symbols and the easter eggs. You’re obsessive. The movie becomes metronomic, constantly clicking, no matter how much you try to ignore the questions it poses.

Never have I seen a movie constructed in a way that doesn’t impact you in the moment, but instead slowly takes its toll on your psyche, which brilliantly mirrors the power that Tár had over her victims. You cannot fully escape from the power Tár, or, by proxy, Tár holds. The world cannot fully escape from the cycles of abuse without disruptive change, and without spoiling the movie, it’s debatable whether or not Tár truly gets her comeuppance. Abuse doesn’t just go away, it haunts: a person, an industry, a world. Tár is refreshingly pessimistic about uprooting abusive traditions; it doesn’t present us with a happy ending, but accepts that moral corruption is inherent to power, fame, and success. The film’s popularity in film circles indicates a readiness to untangle this, maybe starting by discussing the art-versus-the-artist debate and working their way up. Hollywood and the Oscars are infamously guilty for uplifting the industry’s worst offenders, as poorly as they try to hide it. Read a Tár win as a moment of self-awareness, and hopefully, a moment of change.

TOP GUN: MAVERICK

Although I’m afraid that whatever I say will upset the Miles Teller superfans (spoiler alert: everyone in the movie is only attractive to distract you from the fact that the Top Gun franchise is straight-up military propaganda), the show must go on.

Half-joking cynicism aside, Top Gun: Maverick is thoroughly enjoyable and genuinely a good film. Contrived and flimsy at times, sure, but isn’t that somewhat the point of the franchise? It takes itself slightly more seriously than it should, but for some reason, that’s what makes Top Gun charming. Everything about Top Gun: Maverick made me feel invited into this mission and this family, perfectly culminating in an audience cheering their hardest for what will be the comeback of a lifetime (both for Tom Cruise’s Maverick and the actor himself). The film impressively balances jovial and pressing tones, with the warm lighting, beautiful settings, and sentimental performances of a feel-good Western-rom-com, but sound design so crisp that noises ranging from the zooming of planes to the casual footsteps on an air strip build immense tension. Top Gun: Maverick is an instant classic. Dare I say it’s better than the original?

But really, this is not a nominee for its content. As Steven Spielberg told Tom Cruise, Top Gun: Maverick “saved Hollywood’s ass.” Just when the pandemic seemed to seal the coffin on theatrical distribution after years of being crushed by streaming services, Cruise swooped in on a Super Hornet jet with a must-see-in-theaters spectacle. The film was almost universally popular amongst critics and audiences, earning a 96% score on Rotten Tomatoes and polling relatively evenly amongst audience demographics. Even with the all-time domestic box office charts adjusted for inflation, Top Gun: Maverick takes the #15 spot, grossing over $718 million at the box office to date. I say to date because, despite being released in May 2022, many theaters are still showing the movie. This big-budget, star-studded, action-packed, easy-to-follow, fun-for-the-whole-family nostalgia ride checked all the boxes, returning magic to theaters and butts to theater seats.

Theaters, studios, and industry professionals nationwide knew they had Top Gun: Maverick to thank, and their thank-you card came in the form of six Oscar nominations.

Top Gun: Maverick became the savior of cinemas, and if the Academy gives it the Best Picture Oscar, view it as their way of thanking St. Cruise and his flight crew. This third of Maverick’s great victories would send a clear signal: mission failed, streaming services, you’re not operating this plane just yet.

TRIANGLE OF SADNESS

In 2022, we saw a boom of “Eat the Rich” movies. The Menu, Knives Out: Glass Onion, Tàr, and Bodies Bodies Bodies all took turns at tearing into class disparities and the wealthy (with The Menu doing so literally). But Triangle of Sadness, I would argue, is Eat-the-Rich-movie royalty, if that’s not too ironic. Triangle of Sadness is a takedown that is so sharply hilarious that, even after 149 minutes of watching, I wanted to come back for more. Greedy of me, huh?

Triangle of Sadness could not be more clearly set in the modern day, following a model-influencer couple, the wealthy elite who accompany them on a luxury yacht, and the crew intent on providing the best service possible to their guests. And then, a storm hits. The yacht capsizes. This ridiculous group of people are shipwrecked and must survive on what appears to be a deserted island. No hope, no Instagram.

The film is thoroughly entertaining and invites interaction. Even if you are a Ken-Langone-level capitalist, you practically want to jump through the screen to break up Carl and Yaya. And even if you are determined not to take away a single socioeconomic argument from this brilliant film (good luck with that), you can sit back and enjoy the sheer beauty in front of you. I’m actually shocked that Triangle of Sadness was left out of the Best Cinematography category. Every shot, every camera movement, feels so creative and refreshing that you’ll almost forget about the sheer chaos of the plot….almost. But, the joke will be on you. It sure is nice to enjoy beautiful things and take the work behind it for granted, but at what cost?At the beginning of the film, Yaya half-heartedly asks Carl why everything is always about money. He barely has an answer. As much as he says doesn’t want everything to always be about money, it often is. We think we’ll be happier at the top, but when the ship sinks, so does the power of a wallet. Triangle of Sadness represents the 2022 storytelling trend of giving the rich and the conceited their dues in the Best Picture category. I know I said no predictions, but a win for Triangle of Sadness would just see more irony play out. Rich people awarding a golden statue to a movie about how ridiculous rich people are? I’m not sure if it would legitimize or delegitimize the film’s arguments.

WOMEN TALKING

Women Talking goes right up next to Rosemary’s Baby (1969) and The Stepford Wives (1975) on my list of films that remind me how scary it is to be a woman.

Inspired by true events, Women Talking follows the women of an isolated Mennonite community as they determine whether or not to stay or leave their colony after learning that the men have been using cow tranquilizer to overpower and rape them.

The scariest parts of Women Talking are not the women’s observations of powerlessness and violation expressed in their monologues. The parts that chill to the bone are the moments in which the women laugh and the moments in which they experience traumatic flashbacks and then quickly recover. These moments remind us that the women don’t have a choice but to remember, to accept, and to process the traumas inflicted upon them. There is no going back, there is no revising the past with present observations. They must carry on after experiencing unimaginable pain and horror.

Women Talking may be heavy-handed in its references to third wave feminist thought that have somehow taken root in this ultra-conservative colony, but you’ll excuse it, as the horrors of having your autonomy slowly stripped from you take root. It is a film that seems to respond to the overturning of Roe v. Wade and directly affirm a woman’s right to make choices about her own body. It reminds us there is no true safety for women in a patriarchal world, not even in the most isolated communities. But in this post-Roe film, the women help each other navigate, folding each others’ hands to make navigation fists, lifting up each others’ arms, and singing, walking, and choosing together. Protest need not be loud, just disruptive.

As abortion laws have been overturned across the country and debates regarding a woman’s right to choose have only become more heated, Women Talking is the nomination that represents mounting anxieties—no, sorry, we’re past anxieties; I mean fears—about what is to become of a woman’s right to choose anything. A win would hurl this debate even further into the spotlight. If the majority of the Academy is horrified, and if they express that on national television in a room full of stars, maybe this cry for help won’t be subdued.

It will be interesting to see if the dominant themes of 2022—domestic anxiety, political tension, the morality of war, and community as family—carry into the films of 2023. It will also be interesting to see what the 2024 Oscars uphold as well-made, important theses. So at least until then, I encourage you to explore how our new releases reflect our beliefs, joys, fears, structures, relationships, and world. Films, with or without a trophy attached to their name, are beautifully-presented arguments; they are tools we can use to better understand the world around us. Little gold men don’t just curate our to-watch lists, but further legitimize their messages’ importance.