Ada Limón & Vulnerability in Poetry

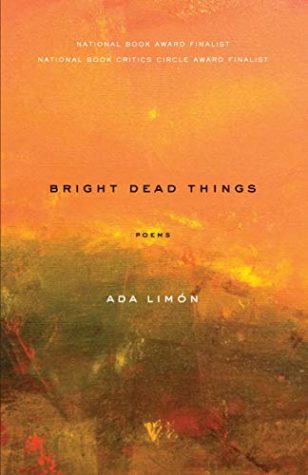

“Bright Dead Things”: A Soul-Bearing Collection Focused on Home and Belonging

In her collection “Bright Dead Things,” Ada Limón finds a unique way to express her own vulnerability and explore the nature of home and belonging: by showing us the world through her eyes. Limón’s use of natural imagery might appear insignificant at first glance, but it is crucial throughout her collection. By personalizing her surroundings, Limón finds common ground with the reader and creates points of relatability that bridge beyond context, gender, and culture. With shameless humanity and knife-like honesty, she provides a window into how she processes the world around her that forces the reader to experience the world in a novel way.

Limón has been honored with multiple awards, including her recognition as the 24th US Poet Laureate. She has also received a Guggenheim Fellowship and has been a finalist for the National Book Award. Even though she is a very decorated artist, however, her poetry is both cutting and warm in its approach to the world and to herself. Her perspective has been shaped by her upbringing in California and tempered by her current residence in Lexington, Kentucky. Her poems are both fierce and soft as she describes heartache and desire, touching on things rarely spoken aloud.

In “I Remember the Carrots,” Limón uses her family’s gardening plot as the focus:

And so I ripped them all out. I broke the new roots

and carried them, like a prize, to my father

who scolded me, rightly, for killing his whole crop.

I loved them: My own bright dead things.

I’m thirty-five and remember all that I’ve done wrong.

Yesterday I was nice, but in truth, I resented

the contentment of the field. Why must we practice

this surrender? What I mean is: there are days

I still want to kill the carrots because I can.

This excerpt captures Limón’s distinct eye and her deft touch with language as she places her past into her current life at age 35. Her concluding line defines the angst often experienced by the growing young adult and suggests her belief that we should never “surrender” along with her understanding that there are days when everyone still wants to reexperience the freedom of their youth. Limón’s focus brings her current maturity into the world of a young daughter, who, not confined by responsibility or “knowing better,” is able to make mistakes, at a time when the consequences are less severe. She understands the attraction—and potentially the inevitability—of the desire to feed into her child-like wonder by “killing the carrots,” even if she may not be able to anymore.

In “What Remains Grows Ravenous,’” Limón comments on another universal fear while personalizing it through her own eyes: “I’m afraid I won’t do the right thing in the face of disaster… or I’m afraid I will be stupidly brave.” She examines this fear by delving into the loss she and her father felt at her mother’s passing:

When my dad became a widower, women brought meals, and wine, and pies.

The word widower looks like window.

Something you can see yourself in, in the dark.

The insight and use of language continue to drive the underlying theme of love and loss. Limón intertwines these two themes throughout her collection. She uses her own personal experiences to conduct a broader truth for her readers. She does this with an openness and courage rarely seen.

In “Accident Report in the Tall, Tall Weeds,” Limón addresses another trauma: “My ex got hit by a bus.” This time, however, she examines her own complicated reaction in a tone of satirical humor, ultimately returning to the recurring theme of small things as a safe haven. She confronts herself: “I swear I never thought it. No seed of transportation deviance. / No tampering with the great universal brake wires.” Limón anchors her humor by telling personal insights that enable the juxtaposition of herself with the world around her. Over the course of the poem, her introspection evolves from a basic understanding of who she once was—“I used to pretend a lot. I’m very good at it”—into a deeper openness to her own self-perceived failings: “I imagine the insides of myself sometimes-/ part female, part male, part terrible dragon.” The poem ends, hauntingly, with the universal TV voice that says, “Stay safe and seek shelter.”

“Bright Dead Things” is a must-read for everyone torn between love and loss, journeying through self-discovery. It can help us understand the impact of the past on the present, and realize both the universality and uniqueness of each of our experiences. Limón bares her soul to her readers in a way that truly allows us to feel that we are not alone, either in our inner mind or outer world.