The Mind of Mrs. Carson

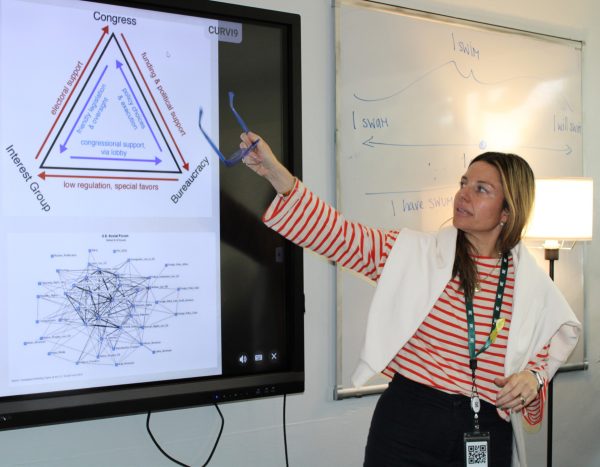

Mrs. Carson in her usual spot, one of the tables outside Cameron.

“If you want to find out who I am, we’re not going to look at the smaller actions, we are going to look at the deeper thoughts, and… I think a lot.”

Everyone has seen Mrs. Jenny Carson ’03 around school, usually by the tables outside Cameron. She has worked here for eight years, and even attended RE two decades ago. She teaches American History, AP Psychology, and the new Ethics courses, which she created. Most people know her, whether it is from being in class with her, St. Alban’s Day, or getting dress-coded by her.

Considering the courses she teaches, I knew it was going to get philosophical. Little did I know that my questions about her passions would lead into a deeply personal 45-minute discussion about how her mind works. It ended up being exactly what I wanted: To reveal something nobody knows about a prominent figure at our school. The following conversation is about how she developed her beliefs, and her beliefs about belief itself.

M.T.: Let’s start at the beginning. How did you figure out what you were passionate about?

J.C.: I graduated in ’03. By the time I was a senior, I knew that I had a passion for the humanities, and I went on to a liberal arts college that fostered that passion. I’ve always been driven by the question, ‘what makes people who they are’? From around my teenage years I was interested in why people believe what they believe and what makes them make the choices they make. To me that is the essence of what the humanities are trying to figure out. That drove me to become a comparative religion major and environmental science minor, because I was curious about how people perceive the physical world but also the metaphysical world.

M.T.: Do you think you’ve come closer to understanding or answering this guiding question?

J.C.: I don’t think I approach it as a problem to be solved, but rather as a fundamental question to guide my thinking. I don’t know that I’m looking for an answer, I’m just looking to constantly know more. I suppose that I’m constantly learning, and that’s the most true thing I can say because everything I learn leads to more questions.

M.T.: So how did this develop in college? After college?

J.C.: So I went to Trinity college for 4 years, and then I lived in Boston for a ‘gap year’ where I worked in the special education departments of high schools. I knew that wasn’t a forever career. Then I went to graduate school, at Princeton Theological Seminary, getting my master’s in divinity, while simultaneously doing a joint degree with Rutgers, getting a master’s in social work. During that time I was also working part-time in nonprofits. I did counseling, I worked in a hospital, and I worked as a social worker in Trenton, focusing mainly on older adults. I thought that’s where my career was going to go. I thought it was going to be in nonprofit management with a focus in older adult programming.

M.T.: What drew you to older adult programming?

J.C.: I find people fascinating, and I think that there is so much opportunity to provide life in a space that people think about as heading towards death. I don’t know, it just always was a space that made sense to me.

M.T.: Would your job involve talking to people?

J.C.: Yeah, so, a big part of social work is learning people’s stories and developing trust. Once you forge trust you are able to help them. One of our greatest misconceptions is that we know what is best for others, and the reality is that mostly we know what is best for ourselves. In order to help somebody who needs help, you need them to trust you, and engaging in their stories can help you help them find what they actually need. It was extremely fulfilling… If I were bilingual I would probably still be doing it here in Miami.

M.T.: Is this your dream job? Or do you think there is something else coming your way?

J.C.: I went through several jobs when I came down here, and I learned a lot. I am a firm believer that in every job you take, you will learn a lot about yourself and something you will take with you, even if it’s a transient position. When this job opened up, in some respects it was unexpected and in some respects it was probably something that was right for a long time. I don’t think I really believed I ever would become a teacher, but there are also a lot of elements of this job that were things I was missing in other careers that I would get here. It’s the right place for me.

M.T.: So, tell me about some things you do outside of school.

J.C.: I’m an avid reader. I mostly listen to books on tape, but I’m constantly consuming literature, and I often needlepoint at the same time. I spend a lot of time focused on family, and I’m involved in my church, and I’m engaged in volunteerism, I like to bake… I think those are the things that make me tick. Oh, and I love to travel; it’s basically what I work for.

M.T.: Would you say that all of these parts are what make up who you are? Or would you consider them separate selves?

J.C.: I think at the core of it all, I love to learn, and I pour myself into what I’m impassioned about in order to be the best I can through learning what I can and then applying what I can learn to my life. I don’t know if that really answers your question, but I am constantly working to be self-actualized (with the fear of sounding like a humanistic theorist); all these things are elements of ways I do that.

M.T.: Why are you distancing yourself from humanism? Tell me about your core values, or belief system.

J.C.: Well, I disagree with a lot of parts of humanism. As for any theories I believe in, I have yet to say there is one truth… I don’t think there’s a truth that is universal. The reality is that we are all human and so we are all flawed, so therefore there’s no possibility of perfection. So how can I fully agree with any theory that would suggest that there is perfection and truth? I think that a fundamental part of being human is learning and growing, so how can we have achieved perfection in order to profess it? And I think that we always have the opportunity to change; while I feel relatively stable and secure in the person I am now, I believe that I could be a very different person in 10 years. It’s a matter of what experiences I go through and how I process them in order to healthily move forward.

M.T.: This got really meta. Dr. Margini warned me that you would try to talk more about the big-picture rather than about yourself…

J.C.: Well that’s just how I think. I guess Dr. Margini knows me better than I thought he did. I think that is, if you want to get down to the core of me, that’s what all of this is, right? And so, if you want to find out who I am, we’re not going to look at the smaller actions, we’re going to look at the deeper thoughts, and… I think a lot. That doesn’t mean I don’t have enjoyable moments of being in the present and laughing, you know? This weekend I went ice skating with Maureen. I was very present in that moment, and it was wonderful. But the way my mind works? That’s very heady. In some ways I think it would be easier to be less heady. There is a quote that we’ll talk about in Ethics that says, “Would you rather be a happy pig or an unhappy Socrates? What is happiness?

M.T.: Well, what is that answer for you? Which would you rather be?

J.C.: I mean if those were my two choices, I’d probably be the unhappy Socrates. But I’d really like to be a happy Socrates.

M.T.: What is the difference between a happy and an unhappy Socrates? Is Socrates unhappy because he is constantly thinking? Because he can’t be satisfied or answer all of his questions?

J.C.: I think that’s what the quote is getting at, but I believe that happiness and knowledge are not the same thing. Feeling really comfortable in yourself and living a life that abides by what you think is right is going to bring you happiness. And so, for me, I would say that’s not happiness, but satisfaction? I think that knowledge just opens doors to thinking, and since I can’t turn off my brain, I just want to learn more. But that’s inherently part of who I am, so if that was dissatisfying to me I would live a very uncomfortable life. I definitely did not always think like this. I think I was a very different person in my youth. At some point I made a choice; there were a lot of ways my life could go. I made a very intentional choice, and it’s made all the difference. I think that we have the opportunity to make choices, but I don’t think we have free will.

M.T.: Explain.

J.C.: I think we are bound by the restrictions that life presents us, and within those restrictions we can make choices about how we wish to live. Like, I can’t change the way my mind works—I know we can to some extent; we have neuroplasticity—but my brain is a thinking brain. There are some people’s minds that can just stop, but mine doesn’t.

M.T.: What do you mean by stop?

J.C.: I can’t stop thinking about bigger things just because I want to relax. But to be honest, I derive joy from it. Surface-level conversations might be relaxing to some people but not to me, and that’s my restriction. And restrictions aren’t necessarily a bad thing. They are just boundaries.

I’m not a very good ‘Humans of RE’ person to interview.

M.T.: Why do you say that?

J.C.: I’m just too heady. You were probably supposed to answer questions like “what is my favorite food”? If you want me to answer your questions more simply, I can.

M.T.: No thanks. That wouldn’t be a very interesting article to read.