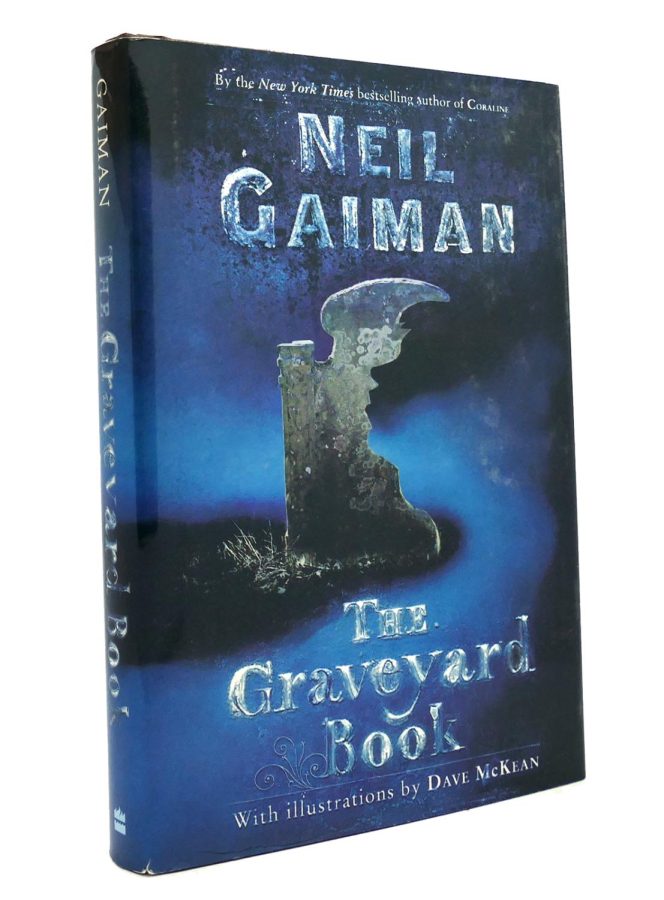

“”The Graveyard Book”: A Fairy Tale for All Ages”

Neil Gaiman’s “The Graveyard Book” is the ultimate fairy tale, not simply because it evokes and pays homage to all its literary and folkloric predecessors, but because it portrays the simple truth of growing up. I will not invoke the terms maturation or coming-of-age, because the book offers no resolution for the character of the protagonist. When Bod (more on that name in a minute) leaves the graveyard in which he is raised at the novel’s end, he is still very much a child. Gaiman, then, spins us a wonderfully macabre story, not of a boy becoming a man, but of a boy being a boy, with all the transformations such a dynamic state entails.

“The Graveyard Book” begins, as many stories do, with a murder. Several murders, actually. The text starts: “There was a hand in the darkness, and it held a knife.” This hand kills the mother, father, and daughter of the Dorian family, who do not factor into the story beyond the opening scene. Gaiman never cheats his reader on account of the age of his genre’s intended audience; although readers never see blood spilled, the violence is palpable, and the stomach turns when the implications of the wet blade and handle are revealed.

The assassin, called Jack, fails, however, in his main task: to kill the baby boy, who improbably escapes the house on the night of the slaughter, and wanders into the nearby graveyard. Ghosts agree to raise the boy—whom they name Nobody, Bod for short—at the suggestion of Death herself. The graveyard is a world of fog and shadow, of gaunt sculptures and gravestones, of stone chapels long abandoned (but not, readers soon come to know, uninhabited). But it is also a homely, storied place, with some of its well-meaning dead older than Rome itself. Age and ancient wisdom magnify the difficulty of parenting, as it is hard enough to relate to one’s children without the added gulf of existing on entirely different planes of being. The ghosts, we suspect, realize their privileged position of being able to speak directly to posterity, and consider the wisdom they impart accordingly.

Modeled on Rudyard Kipling’s “The Jungle Book,” the episodic plot sees Bod through several relatively self-contained adventures. There are friends, whom he outgrows as a living, changing boy playing amongst dead, ever-youthful children is fated to do; guardians, including a vampire and a werewolf, whom he disobeys with near-fatal consequences; and belligerent schoolmates, with whom he contends. Each of these experiences embodies what it is like to grow up: to find those whose company we once enjoyed wanting; to go against those wiser than us who only have our best interests at heart; to fight with those with whom fighting seems unavoidable.

Gaiman’s characteristic preoccupation with mythology also plays prominently in the novel. In an especially thrilling chapter, a pack of ghouls abduct Bod and spirit him to their home, Ghûlheim, which seems to Bod “a city that had need built just to be abandoned, in which all the fears and madnesses and revulsions of the creatures who built it were made into stone.” This otherworldly, almost Lovecraftian description gives readers pause to wonder whether we are immersed merely in the author’s invention, or in some other deeper taproot of story.

Gaiman understands the resonance of mythology as well as any living author or scholar, having penned titles such as “American Gods” and “Norse Mythology.” The key to myth is its expansive quality: the sensation, when one reads it, of wonder beyond comprehension. The conclusion of the chapter sees Bod rescued by a werewolf, who bears him on her back across the Milky Way. Gaiman intends that we not grasp the full significance of the events: Bod does not, either. He may tread heaven, hell, and all in between in a single night, but one seldom thinks beyond one’s wonder when one is growing up.

Gaiman’s style depends on economy. His narration is vivid yet unimposing, reducing a scene to its essential components. In his opening, he undoubtedly could have churned out pages upon pages describing how “wisps of nighttime mist slithered and twined into the house through the open door” in imitation of Poe. But to this image he dedicates only a sentence, a short but fitting glance upon the setting, and instead proceeds to narrate the murder at hand, leaving us to fill out the rest of the atmosphere with only one detail to guide our way. And yet, as if a spark has fallen on a pile of dry and graying leaves, the scene is illumined. Reading that sentence, I see mahogany door frames and obscure photographs lining the wall that flanks the staircase. The shadowy outline of a chandelier hangs from the ceiling; the light of the outdoor street lamps diffuses through the “nighttime mist,” and by it I see the razor gleam of the knife held in the dark.

In his dedication of “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe” to his godchildren, C. S. Lewis remarks that “some day you will be old enough to start reading fairy tales again.” When we are young, we experience fairy tales. To read as one who has only recently become familiar with the fundamentals of language is to feel excitement, fear, joy, triumph, grief, and reflection. When we are older, as Lewis observes, we read fairy tales; we return to them with a critical eye, no longer beholden to our emotions. But every high school literature student has, at one time or another, expressed disappointment at the binarism this more “literary” kind of reading sets up. To be liberated from our emotions seems also, in a more tragic sense, to relinquish them.

I believe this argument flawed. It ignores the most gratifying type of engagement with a text, one that achieves parity between reading and experience. I believe that by taking up fairy tales at this propitious intermediary stage of our lives—at stage in which we are old enough to read fairy tales critically yet still young enough to feel their power viscerally—we can train ourselves in this type of engagement. We can practice the discernment that comes with growing up without forgetting what it was like to grow up: to be dazzled, beguiled, enraptured.

That is another purpose of reading fairy tales at an older age: to not forget, to remember. Only in remembrance of what we have gone through may we look joyously to what lies ahead. In one of the tenderest of the novel’s chapters, when Bod dances with Death herself, our fear of the future melts away. We are like Bod, we think, as we read and finish the book. And if he can look upon Death, and smile at her, and dance with her, and look forward to seeing her again, why must we be afraid?

So here is to “The Graveyard Book”, the greatest of fairy tales. We close the book, and we put it on the shelf, standing, stretching, wondering where the time has gone. But we are not concerned; we are only hopeful. We depart our reading room and walk into Life, as Bod does, “with his eyes and his heart wide open.”