How 9/11 Transformed Rock Music

The year is 2011. Bush’s War in Iraq is coming to a screeching halt. It’s been 10 years after the events of 9/11, and an entire generation is growing up not having seen the planes hit. You’re part of that generation, and as you sit in the 9/11 assembly with one earbud in, you realize: Foo Fighters haven’t released any good music in years.

For decades, the ever-changing art form that is Rock has shapeshifted to accommodate what the American public wants to hear—and sometimes, what they need to hear. The latter half of the 20th century is filled with stories of artists using Rock and Roll to express their thoughts and feelings about America’s social and political environment, turning the genre into a vital medium of commentary and public outcry.

If you look at the charts today, however, you won’t see Rock dominating anymore. Americans have stopped tuning in to what Rock musicians have to say—but more than that, the genre itself has tuned out, abandoning urgent political messaging in favor of escapism.

9/11 was the turning point, and it changed Rock music more than you might think.

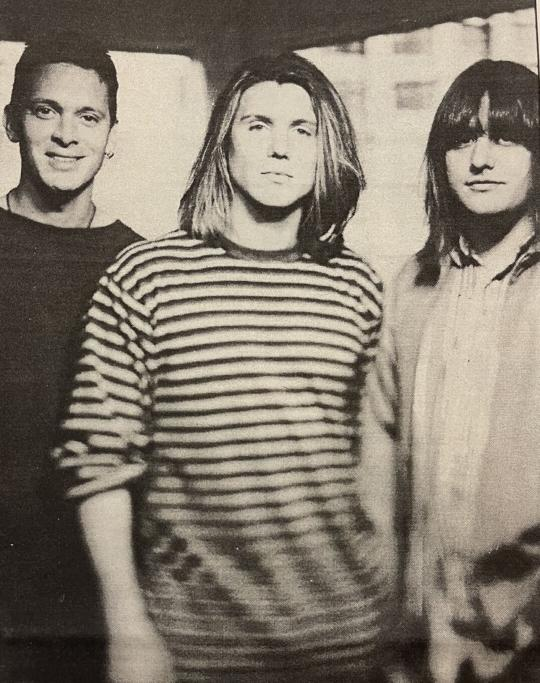

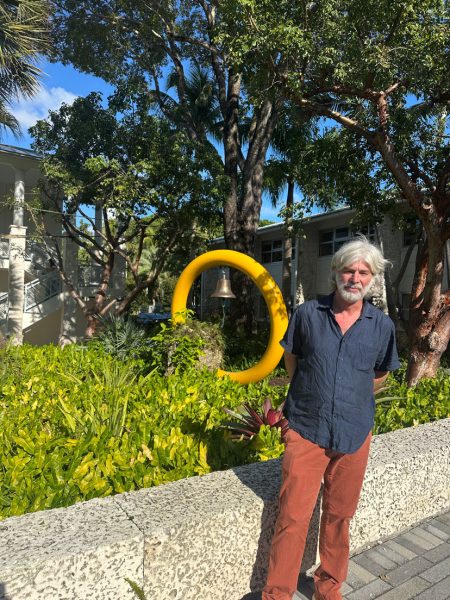

One person who can speak to the history of Rock before and after 9/11 is Mike Malinin ’85, an RE alum and the drummer for The Goo Goo Dolls. The band was formed in 1986, when the sounds of soft rock, metal, and shred guitar were at their most popular. The band released hit albums such as “A Boy Named Goo” and “Dizzy Up The Girl.”

As the ’80s gave way to the ’90s, Rock and Roll continued blossoming with the birth of grunge, a style addressing themes such as social alienation, self-doubt, abuse, neglect, betrayal, social and emotional isolation, addiction, psychological trauma, and the desire for freedom. Bands such as Rage Against the Machine, The Cranberries, Bad Religion, and even Foo Fighters released many songs with heavy political motifs throughout the ‘90s.

When the first plane hit the North Tower on September 11th, 2001, everything changed. Radio broadcasters reported an immediate shift from their conventional pre-set songs to patriotic music. Listeners tuned in to hopeful ballads reflecting their own emotions regarding the national travesty. Music became the go-to escape.

Malinin described playing at The Concert For New York City, a benefit concert at Madison Square Garden in October of 2001. “It was a healing event,” he said, recalling the tension in the crowd as he performed.

Americans were calling out for help processing the recent calamity, and Malinin felt, in that concert, that it was Rock’s job to answer. “Seeing firefighters and first responders [in the audience] smile and sing along to some bands made it feel OK for people to go on with their lives,” he said.

Artists like Paul McCartney, David Bowie, Billy Joel, and James Taylor collaborated to give Rock in America a new purpose: to provide an emotional escape.

As time went on, however, the higher demand for patriotism within pop culture incited censorship within the music industry. According to The Hollywood Reporter, over 165 Rock and Roll songs were banned from radio stations in the immediate aftermath of 9/11.

Malinin felt the danger of this climate of censorship. “It can become a bad thing really quickly if people feel stifled and can’t speak their minds,” he said.

Many bands had to alter lyrics, album covers, and even the content of albums to continue releasing music. After receiving pushback for the political statements made in their 2001 single “New York City Cops,” The Strokes removed the song from their album “Is This It.”. In a 2018 Vulture interview, Strokes lead singer Julian Casablancas said the exclusion of the song caused fans to overlook other political messages in their early songs. “When it was taken off the album after 9/11, the political element got removed from the band’s narrative,” he explained.

These forces molded Rock into a toothless genre during an era when it could have transformed into a new medium of vital political and social critique, as it had in the ’90s. Now, in 2022, Rock is on the back-burner; you would be hard-pressed to find a Rock song on the charts that expresses any kind of political point of view.

Instead, contemporary Rock songs aim for escapism, an idea of what their listeners want to hear instead of what their listeners should. According to Ultimate Classic Rock, Def Leppard’s new release “Take What You Want” is one of the most popular Rock songs of 2022. But it’s also a genre hybrid, incorporating pop and country influences, and its lyrics focus entirely on “taking what you want” in a personal sense.

One notable exception to the irrelevance of contemporary Rock is Roger Waters, the Pink Floyd bass guitarist who has openly used his music to express his distaste for the current political climate in America. Mr. Waters’ performances throughout his “This Is Not a Drill” tour have received widespread pushback, inciting harsh reviews and members of the audience to flee the stadium before intermission. In his performances he includes numerous images of politically charged subjects, including abortion, religion, and the names of murder victims from George Floyd in Minneapolis to journalist Shireen Abu Akleh in Palestine.

In an interview for CNN, Waters explained that his mix of “performing and preaching” is necessary to create a spirit of activism between himself and the audience—something he finds lacking in music today.

During her induction to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Joan Jett once said, “Rock and roll is political. It is a meaningful way to express dissent, upset the status quo, stir up revolution, and fight for human rights.”

The attitude of emotional escapism prevalent in Rock music today is a lasting effect of 9/11. And it’s an attitude that can be found elsewhere, too, not just in music. Avoidance of current issues and contrasting opinions is a key characteristic of many media platforms, including news outlets and curated social media feeds that tell us what we want to hear, re-enforcing our close-mindedness and disconnectedness.

Rock and Roll was once necessary to tell us what we need to hear. Hopefully it will become necessary again.