How “Sorry to Bother You” ushered in a new era of social satire

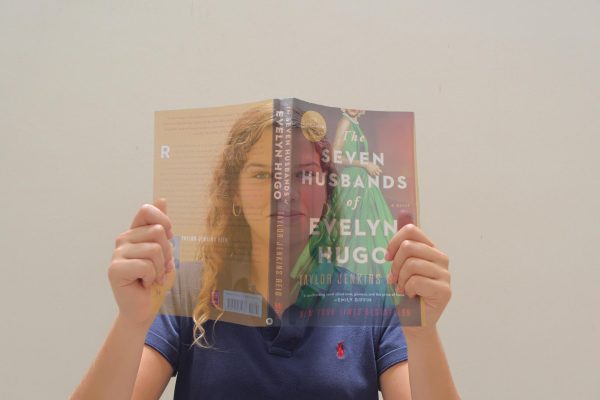

Vox / Doug Emmett / Sundance Institute

Lakeith Stanfield in ‘Sorry to Bother You’

For a film with such a mild-mannered title, “Sorry to Bother You” is anything but.

“Sorry to Bother You” follows Cassius Green, a Black telemarketer living in an alternate version of present-day Oakland, who must use his “white voice” to have a shot at climbing the corporate ladder. As Cassius becomes more successful, he must reconcile his morals with the seeming inescapability of greed, slavery, and consumer culture under late-stage Western capitalism. The film’s cheeky title comes from the classically saccharine, fake-apologetic term telemarketers use to plague our inboxes, even though our protagonist’s increasingly dangerous situation forces him to grow as bold as possible.

The film’s genre is difficult to pin down. It’s absurdist commentary, magical realism, body horror, science fiction, and comedy stitched together. “Sorry to Bother You” is also thematically complex, weaving together commentary on the economy, social hierarchies, and identity. However, first-time writer-director Boots Riley takes a targeted approach to argumentation via film. He injects his script and aesthetics with fantasy, tension, and humor while sharply condemning the connections between social mobility and race. I can almost guarantee that a dystopian finale has never been so colorful or untamed.

Though Riley’s style revels in irony and surrealism, “Sorry to Bother You” is straightforward when it comes to the socio-technological themes it satirizes. In fact, the film’s defiant bluntness revitalizes the genre of the social satire for the modern era.

Although the great social satires of the 20th century (e.g., “Network” [1976], “Heathers” [1989], etc.) were direct in their allegories and, like any good film, creative in their use of visuals to amplify their themes, these movies were prescient, not responsive. Widespread dissatisfaction for the aspects of society they satirized grew mostly after the films’ releases. For example, the 1976 poster for “Network” warns its audience to prepare itself for a “perfectly outrageous motion picture.” Today, journalists often praise “Network” and its prescience for predicting the corporate takeover of news media.

Modern satire differentiates itself by reaffirming a known problem. As humor scholar James E. Caron explains in a 2016 article for Studies in American Humor, “Skepticism toward metanarratives as well as the impact of technology and science on all domains of human society… provide the first necessary ingredients for understanding the production and consumption of contemporary satire in the United States.” This New Social Satire reacts to existing pessimism toward the state of society, and it must do so in memorable ways to encourage viewers to take action to solve a currently existing problem.

The New Social Satire combines the urgent with the memorable. We exist in a world with a short attention span and 24/7 Internet access, where anyone can summon billions of distractions, read the latest anxiety-provoking news, and share their opinions with the push of a button at any given moment. So if an audience is going to remember a film’s message, the filmmakers had better work their hardest to make their lessons stick. Riley did just that. “Sorry to Bother You” is as blunt as it can be in its dialogue and visual style. Riley’s script is packed with dialogue alluding to and directly addressing societal injustices. He even incorporates references to themes in his characters’ names (Cassius Green is pronounced like “cash is green,” which is a reference to common dismissals of systemic racism that say that anyone, regardless of skin color, can make the same amount of money just by working hard enough in America).

To further accentuate the themes in his script, Riley uses visual surrealism to his advantage. A video essay by H2Mass discusses the cinematography’s focus on three main colors (yellow, blue, and green) in the film’s palette to symbolize the interplay among advancement, stagnation and tension, respectively. But even without color theory, one can see that every hue is brightly saturated – Riley wants his film to visually pop. Riley also breaks the laws of space and physics to mark transitions in Cassius’ development, as Cassius is literally dropped into peoples’ homes when he calls them, and Cassius’ home decor breaks to reveal improved models as he earns a higher salary. Riley creates corporate environments that look plastic, curated and unnatural, contrasting messier, more casual domestic settings. And, without spoiling anything, the hybrid creatures we see towards the end of the film were made with mid-range CGI technology, which emphasizes their not-quite-right look in conjunction with the corporate immorality that leads to their existence. These tactics all combine to create a delightfully shocking and incongruous style that grabs your attention and refuses to let go.

After all, if you can easily remember the look of the film, you are more likely to remember what it was saying.

But through Riley’s disorienting sound mixing, we also remember how the film says its ideas. Riley hired white actors to dub Lakeith Stanfield, Tessa Thompson, Omari Hardwick, and Danny Glover’s voices to emphasize the absurdity of linguistic racism in the workforce and the unnaturalness of the “white voices” adopted by the Black characters who want to advance their careers. In film, the sounds emphasized in the mix can modulate the mood, and when Patton Oswalt’s voice plays over a shot of Hardwick speaking, we may initially chuckle, but a creepiness and strangeness sets in. In the film’s alternate reality, however, this white voice is plausible. Just like its cinematography, the audio of ‘Sorry to Bother You’ invites us to laugh at its absurdity before normalizing its world’s more shocking features, leaving us to sit in discomfort.

‘Sorry to Bother You’ was one of the first films created in the vein of this newer, blunter kind of satire. Two years later, “Promising Young Woman” (2018) (another personal favorite) would develop into a candy-coated #Me-Too era vengeance film that incorporates traditionally feminine aesthetics, clothing, and pop songs to accentuate the lack of female perspective in prior rape-revenge movies. Against pastel scenery, the film’s biting dialogue and dark subject matter have a larger capacity to shock and captivate the viewer. Most recently, “Don’t Look Up” (2021) used a script teeming with situational irony and an all-star cast to draw attention to the very-urgent issue of climate change. Both films are a part of this new wave of satirical filmmaking that, in a world with constant distractions, feel the need to opt for the blunt over the subliminal.

Notably, “Sorry to Bother You,” “Promising Young Woman,” and “Don’t Look Up” all attracted extreme controversy upon release. Like most movements within a genre, there are traditionalists who would rather preserve subtlety. But the New Social Satire responds to urgent, currently occurring problems. It has no time to hide messages behind symbols and cryptic dialogue.

So why watch “Sorry to Bother You”? A modern satire through and through, the film argues with artistic indelicacy indicative of a shift in genre. The cinematography and comedy make the film stand out and are reasons to watch it in and of themselves. If you’re interested in how filmmakers have become accustomed to crafting arguments in a world consumed by the elements they criticize, that’s another good reason to watch Riley’s ultramodern social allegory. But you should really watch to immerse yourself in the commentary and be outraged about the truths Riley presents regarding systemic racism in America. The best films disturb and move us, and no genre is as directly unnerving and revealing as modern social satire.

Let the film bother you. You’ll quickly realize that this satire refuses to let you send its message straight to voicemail.