What killed Rock & Roll?

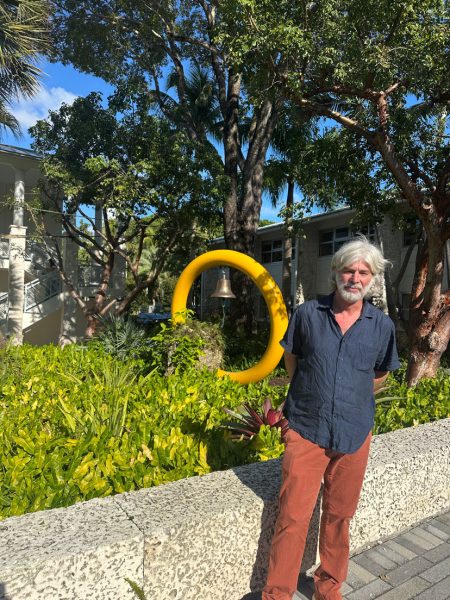

Jessica Weinstein ’22 headlines a Rock 4 Relief concert in front of a packed crowd.

From the mid-1900s to the early 2000s, one type of music stood out from the rest: Rock & Roll. It set the stage for social commentary and rebellious exuberance, ultimately leading to changes in not only the music industry, but the political and cultural spheres as well. Yet the genre has fizzled out of pop culture in recent years. The first rock song in Spotify’s most streamed songs of 2021 is found at spot 17, with only three in the top 50.

Defining rock is admittedly difficult, as the genre has evolved from the simpler and less diverse Rock n’ Roll of the mid-20th century into a massive subset of genres, including anything from alternative rock to death metal. Typically, however, rock consists of a live band that includes a singer, guitarist, drummer, bassist, and possibly a few other musicians.

So, what ‘killed’ rock? Well, the answer to that question is multifold, but it can be boiled down to a few popular theories.

The first comes from Performing Arts Department Chair and Band Teacher Mr. Jon Hamm, who insisted that “it’s not a theory,” but rather “empirical knowledge.” Mr. Hamm has experience working as a professional musician in Miami since the 80s, and thus has seen much of recent musical history unfold firsthand.

“I would play at the Fontainebleau and the Eden Roc and the Ritz Carlton,” Mr. Hamm said, as he explained the Miami music scene in the 1980s. “If you wanted to compete for a restaurant in those days, you had a four-piece band, because if you didn’t, then you didn’t get the business.” But this traditional “club date” society would soon change drastically.

“The first thing that happened was that they learned how to split the keyboard. So, with the left hand, the keyboard player could play the bassline. Quartets started dropping down to trios,” explained Mr. Hamm. This development sparked the transition into smaller performance groups. “Then not long after that, about the same time, came the sequencer. With the sequencer you could do a lot of things with music—it was basically a disc recorder,” he added. Trios eventually became one person—essentially, a disc jockey.

Coinciding with the rise of electronic production, funding for music education decreased. This drop in funding paved the way for hip-hop music, as aspiring musicians had to find cost-effective ways to produce music. “They had a drum machine, and they had a voice recorder, and then we got hip-hop,” explained Mr. Hamm.

But did the birth of hip-hop truly ‘kill’ the genre of Rock & Roll? I turned to fellow classmate Gabriel Mora ’22, who had a very different outlook.

“I think it’s not so much that rock has died. I think rock has evolved to fit what people want,” Mora said. He explained that in the early 60s, rock was very experimental and linked to the counter-culture, which led to the heavier, more metal bands of the late 70s, the punk movement, and post-punk movements such as grunge. The constant emergence of new musical movements kept the genre interesting, but also slowly led away from the traditional Classic Rock sounds of Jimi Hendrix, the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, or Pink Floyd.

Gradually, “hip-hop has become really popular, and it’s kind of taking over,” said Mora. He agreed with Mr. Hamm’s description of how electronic music has taken command of the industry, saying that “it takes fewer people to produce the music, whereas in rock bands you had to have a guitarist, bass guitarist, drummer, and vocalist.”

For Dr. Brandon King, a music aficionado who teaches history and economics at the Upper School, the explanation lies less with technological changes and more with the evolution of the counterculture that gave birth to rock in the first place. Dr. King grew up in between Mr. Hamm’s generation and the current high school generation, providing a firsthand account of the music industry in the late 80s, 90s, and early 2000s. He listened to mostly rock in high school, describing his connection with rock as “very much an emotional one.” He noted one Limp Bizkit song “that just helped [him] process things so much better than any other song in the world.”

However, in college his taste moved more towards jazz and hip-hop. “I was getting more in touch with my own experience as an individual in our larger economic political social context. So, music that touched on race and gender and identity began to speak to me a lot more.”

Dr. King brought up Rage Against the Machine, a band that bridged the gap between rock and hip-hop, while including intense politically charged lyrics. King stated that the band “was really speaking to this significant change that was happening between boomers and millennials coming of age, but also capturing some of that younger generation X,” in which young people did not want to blindly follow any source of authority. Hip-hop piggybacked on a second wave of countercultural energy, this time with a focus on race, gender, and personal identity.

From the perspective of Rock 4 Relief President Jessica Weinstein ’22, rock is not dead at all—but its place in the landscape of the music industry has certainly changed. She mentioned “seeing rock pop up in the background of pop and rap songs,” such as “Take What You Want” by Post Malone, featuring Ozzy Osbourne on guitar, and Billie Eilish’s rock-inspired “Happier Than Ever.”

Weinstein reminisced for a moment about listening to her dad’s favorite classic rock tunes when she was growing up. “[Rock] is living on in our generation,” she said. “There are people who gravitate towards rock music and want it to stay alive.”