A Page in History

What working on the floor of the Senate for five months taught me about our nation's upper chamber

May 23, 2022

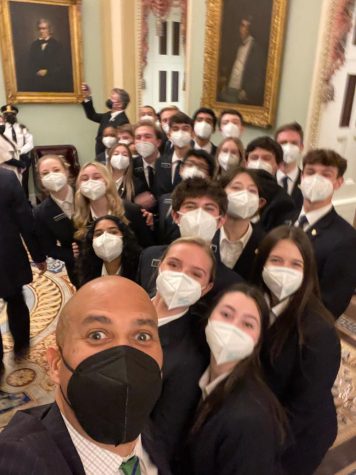

If I told you that I once served the Vice President a glass of water with a Kleenex tissue on top of it, you’d probably think, “Is this kid crazy or something?” Weirdly enough, it’s true. “How?” you might ask. Well, in the summer of 2021, I applied to the Office of New York Senator Chuck Schumer to be appointed as a United States Senate Page. Pages, part of a long-standing Senate tradition dating back to the early 1800s, serve on the floor of the United States Senate, performing myriad tasks including preparing the Senate chamber for daily sessions, delivering correspondence and legislative material, and supplying support to Senators during sessions. After a lengthy admissions process, I was formally selected as one of thirty Pages, all in their junior years of high school, for the Fall 2021 semester. In this piece, I’m going to write about the good, the bad, and the ugly I saw during my five months in the Senate.

First off, I’d like to stress that my experience at the Capitol was overwhelmingly positive. I mean, I had a front-row seat to history – I heard negotiations on President Biden’s Build Back Better Bill, saw former Senate Majority Leaders, Harry Reid and Bob Dole, lying in state, worked the floor during historic debates on voting rights, and had unrestricted access to the Capitol complex, all at sixteen years old. Senators told me jokes, bought me chocolate cake, and helped me with my physics homework. One even sent me on a Capitol-wide scavenger hunt for his lost phone. I don’t think I’ll ever live through a more interesting five months ever again.

There were some quirks to the program, though. It makes sense – it’s not exactly a normal activity for a high schooler. The biggest culture shock was the residential life. I’ve lived with my family all my life. The furthest I’ve ever strayed from them was a month of summer camp. You can imagine, then, the pit I felt in my stomach as I walked into Daniel Webster Hall – a former funeral home turned Page dorm – for the first time. To make matters worse, just as I walked into the building, overflowing duffel bag in hand, an uncontrollable stream of blood started gushing from my nose. It went everywhere. I had to give my clothes a deep cleaning over the next few days.

All that turned out to be nothing compared to what came next. I did what most kids my age would consider unthinkable: I gave away my cell phone to the program administrators, who locked it in a safe for the entire semester. Pages aren’t allowed phones at any point during the program, only receiving them when they check out on holidays. Honestly, it wasn’t all bad. I whittled away at my reading list, explored Washington, practiced guitar, and procrastinated much less. I’ve noticed that I spend less time on screens now, and my time in DC rekindled my love of literature. But being unable to contact friends and family was instantly inconvenient. I could only talk to them late at night after work on my dorm’s landline, and only if one of my three other roommates wasn’t already using it. Also, the landline didn’t reach other countries, so I couldn’t speak to my abuela in Peru or my cousins in Spain for the entire semester.

After turning in my phone, I said goodbye to my mother, met my roommates, unpacked my bags, made my bed, and started memorizing the names and faces of all 50 Democratic Senators for the test we’d need to ace to be able to work. I handled the first of many five-a.m. wakeups with stoic indifference, put on my navy-blue polyester-blend suit (our Page uniform), and headed to the Page School, found in Webster Hall’s basement, for six-a.m. classes. Even though I ran on six hours of sleep or less every day, I found that I ended up learning a lot in the two hours of instruction I got every morning. The teachers managed to cram a full semester of learning into 15-45 minutes per day per class, and it was some of the most fulfilling instruction I’ve ever received. The rigor didn’t compare to RE (of course), and it’s been difficult reintegrating, but I still feel satisfied with the education I got in DC.

After my first few hours of classes ended, the fun began. I walked into the Capitol for the first time, paused to take it all in for a moment, and got straight to work. My Page class’s first week involved many errors. We learned the job on the fly, making plenty of embarrassing mistakes but learning as we went along. I made my fair share of these mistakes, but in the end, I felt confident that I could do the job.

The core idea behind being a Page is simple – do whatever task any adult on the Senate floor gives you – but learning how to be efficient and professional is harder. The Capitol building is a labyrinth of winding corridors, unending basements, and tucked-away offices, so it takes a while to map it all out mentally. Early on, floor staff would send me to relay a message to some office, and I’d wander around aimlessly, hoping I’d somehow appear right in front of it (I never did). Some of my peers got lost in the Senate basement one night while emptying out the recycling. A few wound up on the House side by accident.

Learning how to address a Senator poses its own challenges, too – every member is different, so there isn’t just one formula for dealing with them. For example, Senator Cory Booker always expected a joke, so if you hadn’t thought of one by 9:45 or so each morning, he’d be disappointed. On the other hand, some members wouldn’t say a word to us.

On days when Vice President Harris would come in to preside over the Senate, we’d all stand up on the sides of the walls. We’d have to get her a glass of water, but the Secret Service instructed us to cover the top with a napkin to prevent poisoning. During my first week, I was the lucky Page tasked with doing this. I was thrilled to have the honor, but one thing lingered in the back of my mind: I didn’t know where the napkins were. I tore through the Cloakroom’s cabinets looking for them, but I just couldn’t find any. I did find an unopened box of Kleenex tissues, though. I don’t know if it was the nerves, but I quickly opened the box, took a tissue out, and put it right on top of the glass. It was mortifying. Unsurprisingly, she didn’t end up drinking it.

Some parts of my work on the Senate floor were a little disheartening – I saw partisan bickering, obstructionism, gridlock, and deep-seated tribalism at the highest level of government. What I saw happening nationally was only amplified in Congress. Collegiality was the exception, not the norm. Senators often didn’t even want to stay on the floor while a colleague from the opposing party was speaking, debate seldom happened (speeches given to extract a 10-second soundbite were preferred), and bipartisanship in the legislative process practically didn’t exist. From early September to the end of January, my entire semester as a Page, I saw only one major piece of legislation get through the Senate: the National Defense Authorization Act, a yearly bill that appropriates funds for America’s military and always garners overwhelming support from both parties. Every other notable piece of legislation we thought might have passed either met obstruction or simply didn’t have enough votes.

If anything, seeing this deepened my commitment to democratizing and reforming our nation’s upper chamber. The biggest obstacle I saw to meaningful progress was the filibuster, a Senate rule that requires a 60-vote supermajority to pass most legislation. Proponents of this rule argue that it protects minority rights, forcing deliberation and producing cool-headed legislation. From what I’ve seen, though, all it does is keep the Senate in gridlock, stoking resentment and practically halting the function of our nation’s highest legislative body. An individual senator can simply block a vote on a bill with one phone call, even if the policy has enough votes to pass. Advocates of reform have raised an alternative: the talking filibuster. This measure would allow each senator to speak twice on a bill in question, after which the motion would go to a majority vote. Senators could still delay the passage of bills they have reservations about, but instead of simply placing a hold with minimal effort, they’d have to appear on the Senate floor and lay out their opposition to the bill. This would encourage actual debate, something very rare in Washington these days.

My semester as a Page was one of the most fulfilling and enthralling opportunities I’ve ever had. I’m so grateful that I could see history right on the floor of the Senate. It was a unique, and often weird, experience that I’ll cherish for the rest of my life. I also recognize, though, that we have some work to do to increase the functionality of our legislature and the health of our democracy. Reforming the filibuster is one place to start.