HBO’s “Q: Into the Storm” decodes the growth of QAnon

On March 21st, 2021 “Q: Into the Storm,” a documentary mini-series about the rise and current state of the QAnon movement, launched on HBO. The episodes explain how desperation to protect free speech, political polarization, and the need for a united community have fueled the massive growth of the Q phenomenon, which gained national attention for its role in the Jan. 6 Capitol riot.

QAnon is an anonymous individual or group that posts “Q drops” on the platform 8chan. Today, QAnon has been banned or is “heavily moderated” on several social media platforms, including Facebook, Twitter and TikTok. Q-related merchandise has also been banned from Amazon. 8chan, QAnon’s home, is essentially a place where anyone can post anything, with no restrictions—what Q-followers would consider the quintessence of free speech.

The documentary series explains that QAnon surfaced in 2017, when an anonymous post appeared on 4chan with the user claiming they were a high-level government official with “Q-level” security clearance. It didn’t take long for the user to develop a loyal following of Trump supporters who became dedicated to decoding the “drops”: short, cryptic messages that seemed to be alluding to real-life incidents and people. After 4chan banned Q content and the user was forced to relocate to 8chan, the movement kept growing, eventually constructing a vast shared mythology around the premise that Trump was the only person willing to stand up to an international cabal of child-eating pedophiles. 4-chan-based QAnon precursors such as Pizzagate (the theory that Democrats in Washington, D.C were running a child sex-trafficking ring in the basement of Comet Ping Pong Pizzeria) and GamerGate (a sexist harassment campaign attacking women in the videogame world) were swallowed up by a much larger storyline.

Now, in the wake of Jan. 6, QAnon is both bigger than ever and harder than ever to ignore—much to the frustration of people who aren’t onboard with it.

“They think Jews are lizards,” said Sophie Bernstein ’21. “I don’t know a lot about it, but I think misinformation is being blown out of proportion and that builds the movement.”

“It’s those crazy guys that stormed the capitol. They believe that the Chinese made the Coronavirus to kill their own people and Oprah eats babies to make herself younger,” echoed Jackson Mopsick ’21.

“They have no political goal,” said Mr. Gregory Cooper, recognizing the fact that although QAnon is a movement, it isn’t clear what their movement aims to accomplish.

Mr. Cooper’s frustration underscores the ambiguity of what QAnon actually is. It’s a lot of things: a movement; an FBI-labeled domestic terrorism threat; a bunch of people making up absolutely insane things and convincing others their word is the truth. But what the documentary clarifies is that it is, above all, a community: an online community for people who have felt marginalized by our current society and feel misrepresented by the government. Their violence, hate, and threatening of democracy is inexcusable, but it’s interesting to think about how and why this virtual community was established.

What is a community?

I think of a community as a metaphorical place where people feel they can contribute to conversations and actions of the group, while aligning with the ideologies held by the particular group.

QAnon is a community: not because a bunch of people live in houses next to each other, but rather because people felt they did not have a community before QAnon, and that’s why they joined it. This is the common thread that binds together the active members of QAnon interviewed in the television series: they were not always a part of the extreme right, but they got swept into the movement because they were desperate for a change in their life.

Many Americans cannot relate to the political elites of Washington, D.C, and when Trump became president, he capitalized on that resentment. He spoke directly to Americans, through Twitter and word choice, and he mobilized first time voters.

QAnon was born alongside Trump’s mantra, in retaliation to the past political norm. Washington’s political class seemed to be an untouchable, removed elite, and QAnon used this feeling to garner support. Q’s followers received a simple answer when they asked why they felt the elites in power didn’t care about them: because those elites were pedophiles who ate babies.

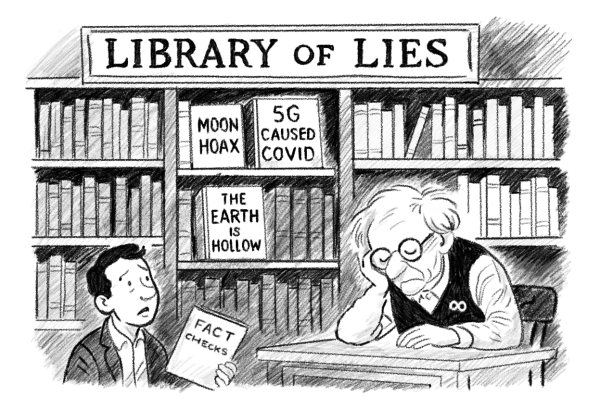

Meanwhile, as the Q phenomenon grew, the media just exacerbated their alienation, both by cozying up to the same elites and by delivering the news in a partisan format. “If you don’t trust the media because you think every network has an agenda, then you end up looking for what you want to find, and then you get to QAnon. If you think everything is fake, you might as well go to the source that tells you what you want to hear,” noted Mopsick.

One of QAnon’s mottos that the series mentions often is “Someone must bring light to the darkness.” Q followers are fueled by this idea of exposing all the “terrible people” in America so that some kind of utopia will grow once our society is rid of the political “devils.” They have been convinced that our society is dark and awful, and that it is their duty to lighten it.

When things go wrong, people search for reassurance, and the Q community has provided this reassurance by taking the blame off individuals and putting it on politicians and certain groups of people.

“It almost makes sense,” remarked Anya Dua ’22. People want something to take out their anger on. And with economic difficulties, especially during COVID, it just makes this extremism worse.”

Thus far, the task of combatting QAnon has mostly fallen to tech and social media companies, who have squeezed it into the tiniest corner of today’s media landscape. Legally speaking, private companies can control who posts on their platform. However, in today’s world, social media is how people use their free speech, and QAnon’s voice has, indeed, been suppressed. Speech that incites violence is not a protected right, but does that mean Q should be nearly silenced by the private media companies that dominate how most people get their news?

Bernstein noted that “it is a weird line to draw about free speech.” She thinks a good alternative to banning is moderating: “Instagram flagging posts with messages that the information may be false is pretty effective.”

Indeed, banning QAnon has not stopped them; it may be doing the opposite. “Instead of someone having a productive, intellectual conversation disproving QAnon’s theories, people yell ‘No! You’re Wrong!’ to Q-followers which makes them feel like they are even more right, and then the violent uprising forms,” Mopsick noted.

Ms. Jennifer Nero, who teaches Humanities at RE, echoed Mopsick’s concern: “I am very reluctant to shut voices down completely. After being shut down, in some ways, QAnon seems more rabid, and more attractive to their adherents. They find other ways to spread their misinformation, so I am not sure if that is the solution.”

What is clear is that a sense of community—a sense of being part of something big, with all the drama and chaos that involves—has been fueling QAnon from the beginning, and the opposition to QAnon needs to be mindful of that. The future of QAnon depends on how we choose to think about it and talk about it.