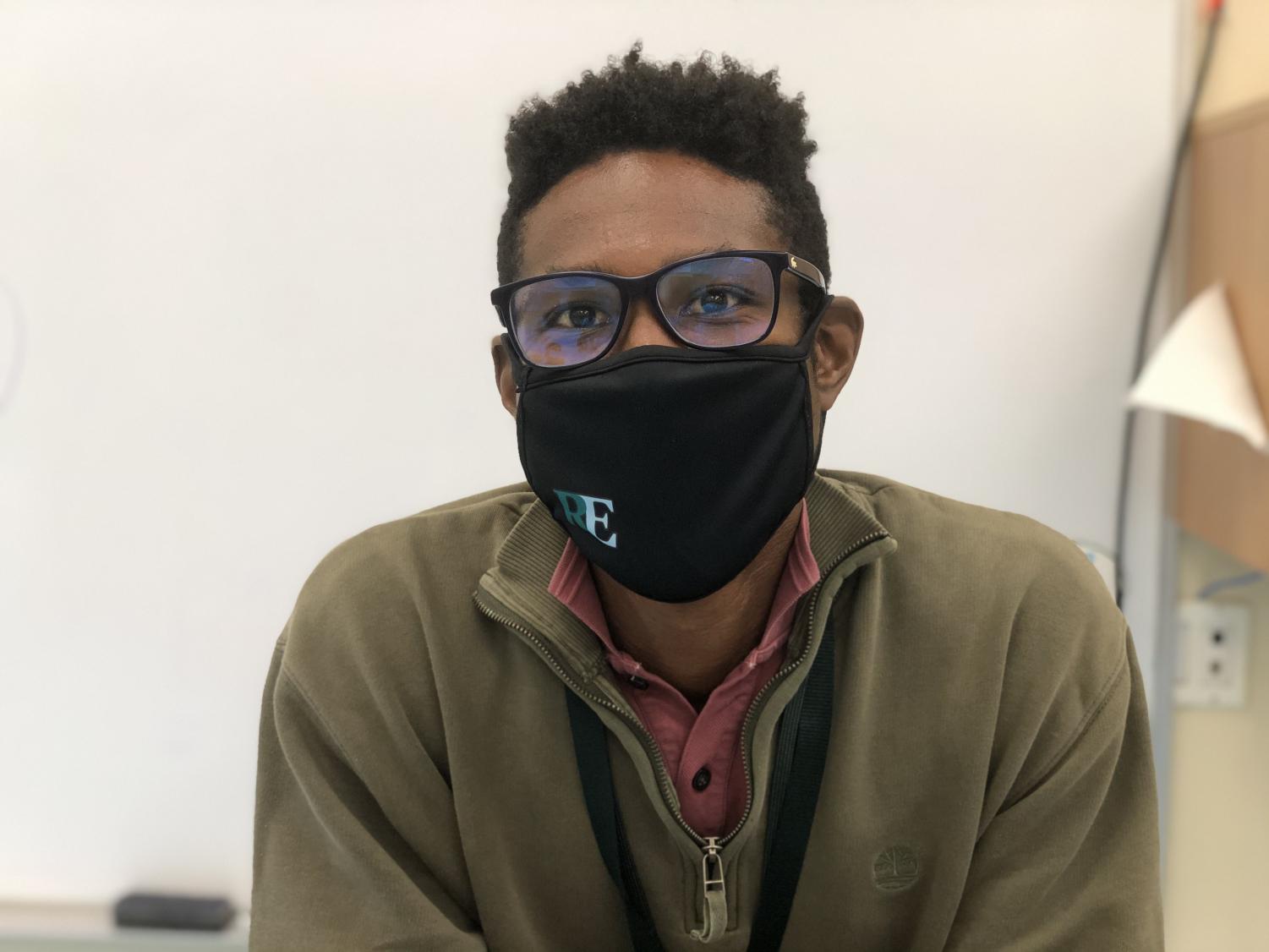

Jackson Mopsick '21 is a staff writer for the Catalyst.

Humans of Ransom Everglades: Dr. Brandon King on his scholarly journey to China and back

March 29, 2021

Currently, nine million Americans are living abroad. Whether it be for education, business, or just for pleasure, all of these people have taken different paths that have led them to live outside of the country. While abroad, people can learn about other cultures, which gives them a new perspective on the world. Dr. Brandon King, an economics teacher who joined the RE faculty last year, is one of the millions of people who have had the opportunity to live abroad. King spent a year in London and almost six years in Hong Kong pursuing a master’s and doctorate—an experience that, in many ways, changed the trajectory of his life.

I recently spoke to King for about 45 minutes. During our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, King and I discussed multiple topics about his life, such as his initial interests in economics, his time spent living abroad in Hong Kong, and what eventually drew him back to the United States.

What drew you to economics?

It is a combination of a few things. I was a high school student who was very interested in business and finance for really one main reason. I saw money as kind of the universal language of the world. Now I know better, but at the time, that’s how I thought. I always thought to myself, I am gonna understand the world a lot better if I understand money. Not just how it can be made but how it moves and how our financial system works. In high school, I was in this program called the Institute of Finance that enabled me to take college classes for business. By the time I got to college, it had become a lot more about understanding not money itself, but how it affects the given conditions, so I got very interested in poverty. Swarthmore is very close to a poor black area of Pennsylvania called Chester, and students would do a lot of tutoring there. So it was through that where I thought being poor is a very different way to live. Even though these students were black, and there was a lot about the way they were living that reminded me of a lot of people that I grew up with, there was a difference between the way I grew up and the way I lived, and it just kept smacking me in the face every single time I went. After that, I said to myself, I’ve got to take Intro to Econ and learn as much as I can about poverty and how it happens and how it affects life.

What type of research did you do about poverty while in college?

I didn’t end up doing that much research about poverty. I was already taking Chinese before I started taking Econ, so I already had a very international mindset when I began Econ. By the time I started with Econ, my mind had moved away from poverty in the United States to disparities in wealth between countries, and how poverty could lead to revolution. I was still interested in poverty, but primarily in a political and social organization context.

What types of countries were you interested in?

East Asia. I knew nothing about East Asia as an emerging part of the world regarding its prominence on the global stage. My uncles heard I was taking Chinese, and they said, “Oh, you’re taking Chinese—this is a great idea! And you’re taking Econ? This is a perfect combination for you. You’re gonna go into business, and you’re gonna make all this money.” So then I thought, ok, I’ll stick with both and see where this goes, and I got very interested in East Asia because of that.

What ended up leading you to move to China?

My first time in China was the year before my senior year in undergrad. And I went out there mainly because I had to. I was a Chinese major in undergrad, and you had to spend some time abroad in China to get the major. So I ended up getting an investment banking internship in Taiwan. When I graduated from college, I thought the internationalist in me was dead. Then I started work. My first job was at Vanguard in Valley Forge right out of college, dealing with funds and people’s 401k’s and all that. I did not enjoy the monotony of that job, no disrespect to anyone in that industry. It just wasn’t for me. I wanted something that challenged my creativity a lot more, and it’s not that that field can’t offer that, but I had a boss who was very straight out with me, and he said, it’s going to take you a while to get to exercise that part of your brain like that.

I decided to leave and go directly to trading. I traded for a while, and I liked that, but I didn’t want to spend every day of the week doing that. I kind of still wanted something else. I found myself kind of envying my friends who were still in undergrad quite a bit. They would say, “I got this project I got to do,” and in my mind, I was like, I wish I had a project. I left that job, ended up being a business analyst for a while. I decided I needed to go back to school, and I’ll come back to finance. I needed to feel the kind of deep interest that I felt in my last semester of undergrad, when I took classical Chinese. So I went back to grad school to get better at classical Chinese, and then I would go back to work at whatever kind of job I could get in finance. Then I just never went back. I learned classical Chinese in my first graduate program. Then I decided, well, I’m not a sinologist, maybe I’m a lawyer. So I ended up doing a specialized law degree in London, where I got an MA in Chinese law. By the end of that, I was like, I don’t want to be a practicing lawyer, but I am academically interested in law, so maybe I’m a future professor. So I found a graduate program that would essentially allow me to be in an interdisciplinary center where I could explore both my interest in Chinese philosophy and my interest in Chinese law and international law more generally. So that’s what brought me to Hong Kong specifically.

What was your time like in Taiwan versus Hong Kong or the different parts of China?

Being in mainland China is very different from Taiwan. Life was easy out there, and what I mean by easy is that it was a lot more comfortable for a foreigner. First of all, the food is great. I was pretty well taken care of by my superiors in my internship. I didn’t have to fend for myself nearly as much as I did in later moments in China. I was really grateful for my time in Taiwan because I think it was the best introduction, particularly as an African-American in China, I could have possibly had. I would say because there was a lot more exposure to Western influence in Taiwan. People seeing me there was far less of a spectacle than it ended up being in mainland China.

What eventually drew you back to the United States?

I was doing some work with e-learning at my alma mater while writing my dissertation. The interdisciplinary center that I was a part of received a small grant to develop e-learning, and they asked me to run the first project. I was thinking I was going to have a future in this e-learning industry, and if they make a nice offer, I’m staying permanently in Hong Kong at my alma mater. Then my supervisor told me that I needed to spend some time in some post-doc centers to raise my profile in the field. I ended up getting a post-doc at the University of Pennsylvania, which is considered a big center in the field. My supervisor told me that it didn’t matter what was going on in Hong Kong, and I needed to go to this big center. That is how I ended back up in the United States.